Reichstag Fire Opens The Road to Dictatorship

In mid-February, there were rumours that the Nazis were planning a “bloodbath” by faking an assassination attempt on Hitler as a pretext for taking revenge. In the midst of this ominous atmosphere, news broke in the evening of 27 February 1933 that the Reichstag was on fire.

Although the origins of the blaze had yet to be investigated, Goering raged: “This is the beginning of the Communist uprising. Now they will strike. We have not a minute to lose!” After the war, Rudolf Diels, whom Goering named head of the Gestapo, recalled:

“Hitler yelled … Now there’ll be no more mercy. Anyone who gets in our way will be cut down…Every Communist functionary will be shot on the spot. The Communist deputies must be hanged from the gallows this very evening. Everybody connected with the Communists is to be arrested. There’s no more taking it easy on the Social Democrats and the Reich Banner either.”

Hitler would not hear of it when Diels said he thought the man arrested, Marinus van der Lubbe, was a lunatic. “This is a very clever, carefully planned matter,” he argued, “The criminals thought this through very thoroughly.”

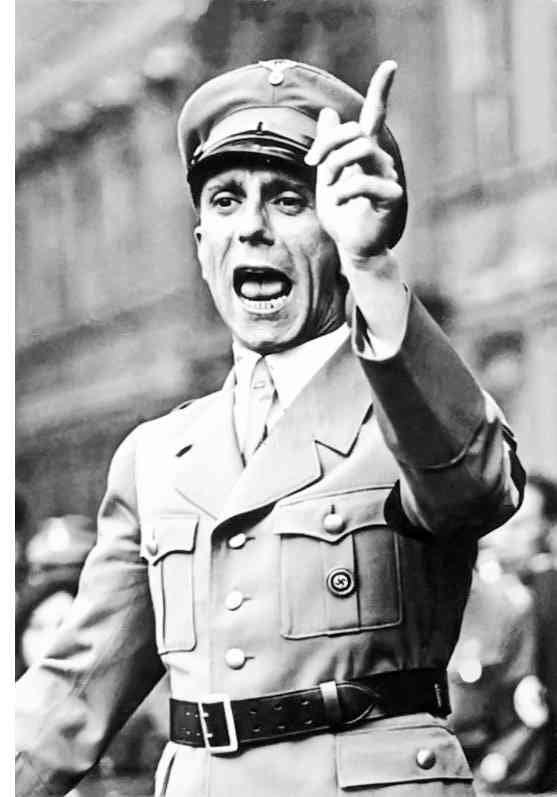

Who was responsible for the fire? The question has never been resolved. What is beyond doubt is that (a) not a shred of evidence showing the involvement of KPD was ever presented and (b) the Nazis were not at all unhappy about the Reichstag fire. On the contrary, it was a welcome excuse to strike a decisive blow against the KPD. Later that evening, when the Nazi leadership assembled in the Hotel Kaiserhof, the mood was positively relaxed. “Everyone was beaming,” Goebbels noted. “This was just what we needed. Now we’re completely in the clear.” As is suspected in the case of the Godhra train fire incident of 27 February 2002 in India, taking all circumstantial evidence into account historians have inferred that the Nazis started the Reichstag fire themselves and blamed it on the communists.

By the night of 27–28 February, the KPD’s leading functionaries and almost all of the party’s Reichstag deputies had been arrested. On 3 March, KPD Chairman Ernst Thälmann was located and detained. The material allegedly confiscated in the Karl Liebknecht House suggested that the Communists intended to form “terrorist groups,” set public buildings on fire, poison the food served in public kitchens and take “the wives and children of ministers and other high-ranking personalities hostage.” Although it was easy to see that this nightmare scenario was a crass invention, Hitler’s colleagues concurred in issuing a Decree for the Protection of the People and the State, which “suspended until further notice” fundamental civil rights including personal liberty, freedom of speech and the press, the right to assemble, and the privacy of letters and telephone conversations.

The decree of 28 February has been correctly described as “the emergency law upon which the National Socialist dictatorship based its rule until it itself collapsed” and as the “constitutional document” of the Third Reich. In a speech in Frankfurt am Main on 3 March 1933, Goering made it abundantly clear what he intended to do with the new powers he had been granted. The measures he ordered, Goering promised, would not be diluted by any legal considerations: “In this regard, I am not required to establish justice. In this regard, I am required to eradicate and eliminate and nothing more!”

As in other cases, here also Hitler faced no opposition from others in the government. Hindenburg had no qualms about signing the emergency decree, which was sold to him as a “special ordinance to fight Communist violence.” Unwittingly or not, he helped transfer political authority from the office of the Reich president to the Reich government.

A Farce of an Election

The U.S. ambassador, Frederick Sackett, termed the elections on 5 March 1933 a “farce,” since the left-wing parties “were completely denied their constitutional right to address their supporters during the final and most important week of the campaign.”

Yet, despite an extraordinarily high voter turnout of 88.8 per cent, the NSDAP came up clearly short of their stated goal of an absolute majority. They got 43.9 per cent of the vote — an increase of 10.8 per cent over the November 1932 election. They registered strong gains in many of those regions including metropolitan Berlin where they had hitherto performed poorly. And it was the Nazis who seemed to have mobilised the majority of previous non-voters.

On the other hand, the SPD took 18.3 per cent of the vote (down 2.1 per cent), and despite everything, the KPD still polled 12.3 per cent (down 4.6 per cent). Notwithstanding all the obstacles placed in their way, the two left-wing parties still managed to capture nearly a third of the vote. Overall, the results demonstrated that left-democratic opposition to Nazism was still quite strong.

Repeatedly snubbed at the hustings, and even the Reichstag fire failing to deliver the coveted majority and thus the authority to rule alone, Hitler now pushed through another set of measures that would make him de-facto dictator, and that too with an apparently ‘constitutional’ sanction. On top of this was the “Enabling Act” passed soon after the election.

23 March: The Enabling Act

The Reichstag met in the Kroll Opera House (the Reichstag building was not usable after the fire) on 23 March 1933 in an intimidating backdrop. As SPD Deputy Wilhelm Hoegner later recounted,

“The entire square in front of the Kroll Opera House was swarming with fascists. We were received with wild chanting: “We want the Enabling Act.” Young men with swastikas on their chests look us up and down insolently and blocked our way. They made us run the gauntlet while they shouted out insults like “Centrist swine” and “Marxist sow”…When we Social Democrats had taken our seats on the outside left of the assembly, SA and SS men positioned themselves in a semicircle in front of the exits and along the walls behind us. A gigantic swastika flag hung at the front end of the grandstand, where the members of the government were seated, as if this was a Nazi Party event and not the session of an institution representing the people. Hitler appeared again in a brown shirt, after presenting himself in civilian clothing two days before.”

The Law to Remedy the Distress of the People and the Reich, as the Enabling Act was officially known, was a bill to amend the constitution. And article 76 of the constitution stipulated that (a) any constitutional amendments had to be approved by a two-thirds parliamentary majority, (b) with at least two thirds of the deputies being present. Since it was not possible to fulfill these conditions depending on the votes of Nazis and their allies, a mischievous plan was worked out. To take care of the first condition, 81 seats held by KPD members who had been arrested under the Reichstag Fire Decree were invalidated. This brought down the total number of eligible mandates from 647 to 566, of which 378 (not 432) deputies would need to vote in favour of the Act. And in order to comply with the second condition, parliamentary rules (which the cabinet had powers to modify) were changed so that “Reichstag members absent without excuse” would also be considered in attendance. Thanks to these manipulations the Act was passed, with only the SPD members (KPD members, being already arrested, were not present) boldly opposing it.

The Act “enabled” Hitler’s government to issue decrees/laws independently of the Reichstag and the presidency. It was permissible for such laws “to deviate from the constitution” and in place of the president, the chancellor was allowed to formulate and publish laws.

The immediate fallout: the KPD having been brutally suppressed with the help of the aforementioned Reichstag fire decree, the regime now took immediate repressive action in response to the Social Democratic parliamentary faction’s refusal to support the Enabling Act. Disappointment and resignation spread among SPD members and increasing numbers quit the party. And then there were many far-reaching, long-term consequences.

First, it gave the cabinet the authority to make laws without legislative consent but in practice this power was vested in the chancellor. The trick was that serious deliberations more or less ended at cabinet meetings and it met only sporadically, so Hitler could do anything in the name of the cabinet. Moreover, it divested the president of his power of issuing emergency decrees over the head of the cabinet. The chancellor was now free to rule as he wished, although Hitler was wily enough to avoid unnecessary confrontation with the charismatic Marshal. For all intents and purposes, Hitler thus became almost a dictator.

Secondly, by driving the last nail in the coffin of the constitution and the parliament, which had already been rendered largely obsolete and useless by Papen and Brüning during their chancellorships, the non-Nazi political parties supporting the bill unwittingly forfeited their raison d’être. What role can political parties play without a representative institution?

Thirdly, the Act, initially limited to four years, was extended three times and remained the basis of fascist rule – of all its crimes against humanity – until the demise of the regime. Given that the Act did not contravene the letter of the Constitution, and that it was actually passed by a majority vote in Parliament, it ended up as a constitutional charter of self-abnegation.

March-April:

Concentration Camps and Economic Boycott of Jews

The draconian powers the government acceded to itself was now vented on Jews on a much larger scale than before. The first concentration camp was established in a former munitions factory near the small city of Dachau in March 1933. Initially, as a state facility, it was guarded by the Bavarian police, but on 11 April the SS assumed command. It became the first cell from which a national system of terror germinated. It was a kind of laboratory where experiments could be carried out with the forms of violence that would soon be used in the other concentration camps. Stories about what went on in this camp acted as a powerful deterrent to opposition to the Nazis.

The concentration camps served another purpose. The heightened sporadic violence perpetrated by frustrated SA men in the wake of the lost election of 5 March (even judges were intimidated; they were afraid for their lives if they convicted and sentenced a storm trooper for cold-blooded murder) was seen by many, including business people, as a law and order nuisance, which the Nazi leadership had promised to solve after the civil-war-like conditions of the past few years. The move from scattered to centralized or institutionalized terror partially solved this problem – partially, because uncontrolled violence on the ground did not stop totally.

The need for state intervention was felt in another area. Few people had responded to repeated Nazi calls for blacklisting Jewish businesses, lawyers and doctors. On the morning of 1 April, SA men took up positions with placards in front of Jewish businesses, doctors’ offices and legal firms all over Germany and tried to get people to participate in the boycott. “The Jewish businesses were open, and SA men planted themselves, their feet spread wide apart, before their front doors,” wrote journalist Sebastian Haffner, who witnessed the boycott in Berlin, in retrospect. “A murmur of disapproval, suppressed but still audible … went through the country”. The British ambassador, Horace Rumbold, observed that the boycott had not been popular but neither had public opinion swung around in Jews’ favour. There were plenty of contemporary stories about customers who deliberately visited Jewish businesses, doctors and lawyers on 1 April. But these people were no doubt a courageous minority. The majority seem to have followed the wishes of the regime.

“And all because they are Jews”

“I feel wicked sleeping in a warm bed, while my dearest friends have been knocked down or have fallen into a gutter somewhere out in the cold night. I get frightened when I think of close friends who have now been delivered into the hands of the cruelest brutes that walk the earth. And all because they are Jews!”

“I feel wicked sleeping in a warm bed, while my dearest friends have been knocked down or have fallen into a gutter somewhere out in the cold night. I get frightened when I think of close friends who have now been delivered into the hands of the cruelest brutes that walk the earth. And all because they are Jews!”

― Anne Frank,

The Diary of a Young Girl

[Anne herself, and her sister Margot, died in the Bergen Belsen

concentration camp in 1945)

Many German Jews were deeply shocked by the first government-organised national anti-Semitic initiative. “I always felt German,” Victor Klemperer wrote in his diary. These feelings were very similar to what the tortured and ostracized Muslims feel in Modi’s India.

On 7 April the regime issued the Law Concerning the Re-establishment of a Professional Civil Service, which not only allowed the government to dismiss state employees considered politically unreliable, but also mandated that civil servants from “non-Aryan backgrounds” be sent into early retirement. On Hindenburg’s request, Jewish state employees who had fought at the front in the First World War, or whose fathers or sons had fallen, were exempted. Once again, the similarity with the current Indian scenario stands out: are not the ‘good Muslims’ spared – even awarded – by the Sanghi government? But it is equally pertinent and necessary to remember too that ultimately, no one who was Jewish or belonged to other targeted minorities was spared in Nazi Germany.

7 April: Governors as Nazi Agents

A candidly titled Second Law for Bringing the States into Line with the Reich, issued on 7 April, installed “Reich governors,” eradicating once and for all the sovereignty of the regional German states. This law gave Hitler the leverage to reorder the power structure in Prussia as well. He himself assumed the authority of Reich governor, rendering Papen’s position as Reich commissioner obsolete. Only three days later, Goering was named Prussian state president, and two weeks later Hitler assigned him the authority of the governorship. The vice-chancellor, who as recently as 30 January had depicted himself as the ringmaster taming the Nazis, had been pushed to the political margins.

April-May: “Trade Unions Forced Into Line”

From his life’s experience Hitler knew that the only force strong enough to stop his cavalry charge was the working class organised under the banner of the Confederation of German Trade Unions (ADGB). So he allowed – rather encouraged – the SA to engage in scattered battles of attrition with this formidable foe, so as to weaken it as much as possible, but deferred the final battle till the time he had more or less finished with all other internal enemies and created the right kind of political atmosphere.

By April, that decisive moment seemed to have arrived. He had neutralised first the communist and then the social democratic functionaries, thereby depriving the working class of mature political leadership; destroyed the organs of parliamentary democracy and the free press; paralysed those who could throw a challenge to his authority from within the cabinet and even the President; monopolised all power in his own hands; had at his beck and call, in addition to the Brownshirts, a Nazified police force and a friendly Army; secured full support of a bourgeoisie that nurtured, until recently, serious doubts about the movement he led; and created an atmosphere of total panic by bloody persecution of Jews and working-class vanguards.

Despite all this, Hitler proceeded cautiously and step-by-step, with a carrot and stick approach, in the final battle against the German working class. Soon after the Reichstag fire, the right to strike was practically abolished; any instigation of strike was subject to imprisonment of one month to three years. Some Houses of the People[1] were occupied by the stormtroops. At the beginning of April, the privileges and rights of the factory committees were restricted: elections were put off; members in office could be recalled “for economic or political reasons” and replaced by members nominated by the Nazis. The committees themselves could be dissolved for “reasons of state”. Employers were authorised to dismiss a worker suspected of being “hostile to the state” without allowing him any recourse to the defence procedure granted by the social legislation of the Reich.

Collective Punishment

[This sentence by Anne Frank, teenage diarist who documented two years of hiding from the Germans and died in a German concentration camp, resonates in today’s world. Try replacing the word ‘Jew’ with Muslim in today’s world, and in India, replace ‘Christian’ with ‘Hindu’.]

“What one Christian does is his own responsibility, what one Jew does is thrown back at all Jews”

― Anne Frank,

The Diary of a Young Girl

Side-by-side with the stick – the sledge hammer would be a more correct description – there were some carrots also. To lull the workers and their leaders before it struck the final blow, the Nazi government proclaimed May Day as a national holiday, officially named it the “Day of National Labour” and celebrated it as it had never been celebrated before. The government arranged for the labour leaders to be flown to Berlin from all parts of Germany. The leaders were taken in by this unbelievable display of friendliness toward the working class by the Nazis and extended full cooperation in making the day a success. Union members and Nazis marched together under swastika banners. Before the massive rally, Hitler himself received the workers’ delegates, declaring, “You will see how untrue and unjust the statement that the revolution is directed against the German workers is. On the contrary.” Later in his speech to more than 100,000 workers, which was again broadcast on all radio stations, he pronounced the motto, “Honour work and respect the worker!” (Narendra Modi has a more concise copy: Shrameva Jayate - Work Will Be Victorious!). In a clever and crafty move, Hitler appropriated the traditional symbolism of 1 May for the German labour movement, attempting to conflate it with the idea of the “ethnic-popular community.”

The surprise attack came the very next day. As planned, stormtroopers occupied union headquarters and took labour leaders into “protective custody.” All Houses of the People everywhere were quickly taken over. A few days later, a law was promulgated for the foundation of the German Labour Front, a mammoth umbrella organisation that brought together all the unions and associations which had been ‘forced into line’, grouping them into fourteen profession-based federations. The Front took in not only wage and salary earners but also the employers and members of the professions. It was not a class organization but a vast propaganda body that proved to be a most effective tool for integrating the working classes into the Nazi state. Its aim, as stated in the law, was not to protect the worker but “to create a true social and productive community of all Germans.” German labourers no longer had a body independent of the government to represent their interests.

The right to strike was finally abolished on 16 May. On 19 May, a law deprived the unions of their right to make collective agreements. From early the next year, the fourteen profession-based federations would be dissolved one after another.

May-June: Liquidating All Political Parties (But One)

After the unions, came the turn of the parties – one by one. Goering confiscated the DSP’s assets on 10 May. In late June and early July, the DSP, the German State Party and the German People’s Party dissolved. Gradually the other bourgeois parties also dissolved themselves under pressure of threats/attacks by the SA and SS, opportunist defection to the NSDAP, or simply because they lost the will to continue. On 14 July, the Reich government issued the Law Prohibiting the Reconstitution of Parties. It proclaimed the NSDAP to be the “only political party in Germany” and made the attempt to preserve or found any other party a prosecutable offence. The one-party state became a reality.

Mid-1933: Grappling With the Unemployment Problem

In his very first radio address on 1 February, Hitler had announced a “massive, blanket attack on unemployment” that was to overcome the problem “once and for all” within four years. However, he was intelligent enough to know that populist rhetoric alone would not suffice, incentives were needed to stimulate a recovery. So in mid-1933 the Law for the Reduction of Unemployment was passed. It allocated first 1 billion and then another 500 million reichsmarks for the creation of additional jobs, particularly in what we call infrastructure development. Other measures were also adopted, such as interest-free “marriage loans” to women leaving the workforce on the day of their wedding. Simultaneously the regime launched a campaign against what it called the “double-earner syndrome,” aimed at forcing women out of the labour market. Nazi patriarchy thus cast its shadow on its economic programme too.

The government also expanded the Volunteer Labour Service, a state employment programme that had been introduced in the final years of the Weimar Republic. All these measures led to some reduction in the numbers of people officially registered as unemployed. The “Reich Autobahn” (a national highway network) was launched later in the year. Hitler personally dug the first turf for the stretch of motorway between Frankfurt and Darmstadt—a gesture with the propaganda aim of suggesting the Führer was leading the way in what was called the “labour battle.” Employment in road construction and the car industry gradually picked up, especially after Hitler mooted the idea of producing a small car suitable for German conditions and the Volkswagen—the people’s car affordable to the working classes – began to roll out and sold in larger numbers.

The strongest long-term stimuli driving economic recovery and the decrease in unemployment came from the rearmament of Germany. “Sums in the billions” would have to be found, Hitler declared, because “the future of Germany depends solely and alone on the reconstruction of the Wehrmacht (The Unified Defence Forces).” The military-industrial complexes would kill three birds with one stone: providing employment, satisfying the national chauvinist ego, and laying the necessary foundation for a war of aggression.

Song of The SA Man

Bertolt Brecht

My hunger made me fall asleep

With a bellyache.

Then I heard voices crying

Hey, Germany awake!

Then I saw crowds of men marching:

To the Third Reich, I heard them say.

I thought as I’d nothing to live for

I may as well march their way.

And as I marched, there marched beside me,

The fattest of that crew

And when I shouted ‘We want bread and work’

The fat man shouted too.

The chief of staff wore boots

My feet meanwhile were wet

But both of us were marching

Wholeheartedly in step.

I thought that the left road led forward

He told me I was wrong.

I went the way he ordered

And blindly tagged along.

And those who were weak from hunger

Kept marching, pale and taut

Together with the well-fed

To some Third Reich of a sort.

They told me which enemy to shoot at

So I took their gun and aimed

And, when I had shot, saw my brother

Was the enemy they had named.

Now I know: over there stands my brother

It’s hunger that makes us one

While I march with the enemy

My brother’s and my own.

So now my brother is dying

By my own hand he fell

Yet I know that if he’s defeated

I shall be lost as well.

“One Opinion, One Party and One Faith in Germany”

After monopolising political power, Hitler redefined certain key ideas. Revolution, he announced to his Reich governors on 6 July, could not be allowed to become a “constant state of affairs.” The revolutionary “current,” he proclaimed, had to be “redirected into the secure riverbed of evolution”, to “people’s education.” Goebbels rendered this idea more profound in a radio address: “We will only be satisfied when we know that the entire people understands us and recognises us as its highest advocate.” The goal, Goebbels stated with utter frankness, was that “there should be only one opinion, one party and one faith in Germany.” (The echo of this goal of uniformity can be heard unmistakeably in Modi’s slogan during his 2014 campaign for the Sardar Patel Statue, calling for “one emotion, one nation, one culture, one voice, one resolution, one goal, one smile”; in the calls by the BJP for a ‘Congress-mukt’ India, which basically means an ‘Opposition-free’ India; and in the attempt by BJP and Sangh cadres to brand any and everyone differing with Sangh ideology as an ‘anti-national’ who should have no place in India.) This meant that all sectors of media, culture and education were to be brought into line with Nazi ideas.

Fascist Patriarchy: Nazi Version of the ‘Love Jehad’ Bogey

One of the key aspects of Nazism was the deterring and prohibition of inter-racial relationships between men and women.

One of the key aspects of Nazism was the deterring and prohibition of inter-racial relationships between men and women.

In Mein Kampf, Hitler accused Jewish men of seeking to deliberately ‘pollute’ the ‘Aryan’ race by seducing, and encouraging Black men to seduce, white ‘Aryan’ women. He wrote, “The black-haired Jewish youth lies for hours in ambush, a Satanic joy in his face, for the unsuspecting girl whom he pollutes with his blood and steals from her own race. By every means, he seeks to wreck the racial bases of the nation he intends to subdue. Just as individually he deliberately befouls women and girls, so he never shrinks from breaking the barriers race has erected against foreign elements. It was, and is, the Jew who brought Negroes to the Rhine, brought them with the same aim and with deliberate intent to destroy the white race he hates, by persistent bastardisation, to hurl it from the cultural and political heights it has attained, and to ascend to them as its masters. He deliberately seeks to lower the race level by steady corruption of the individual…”

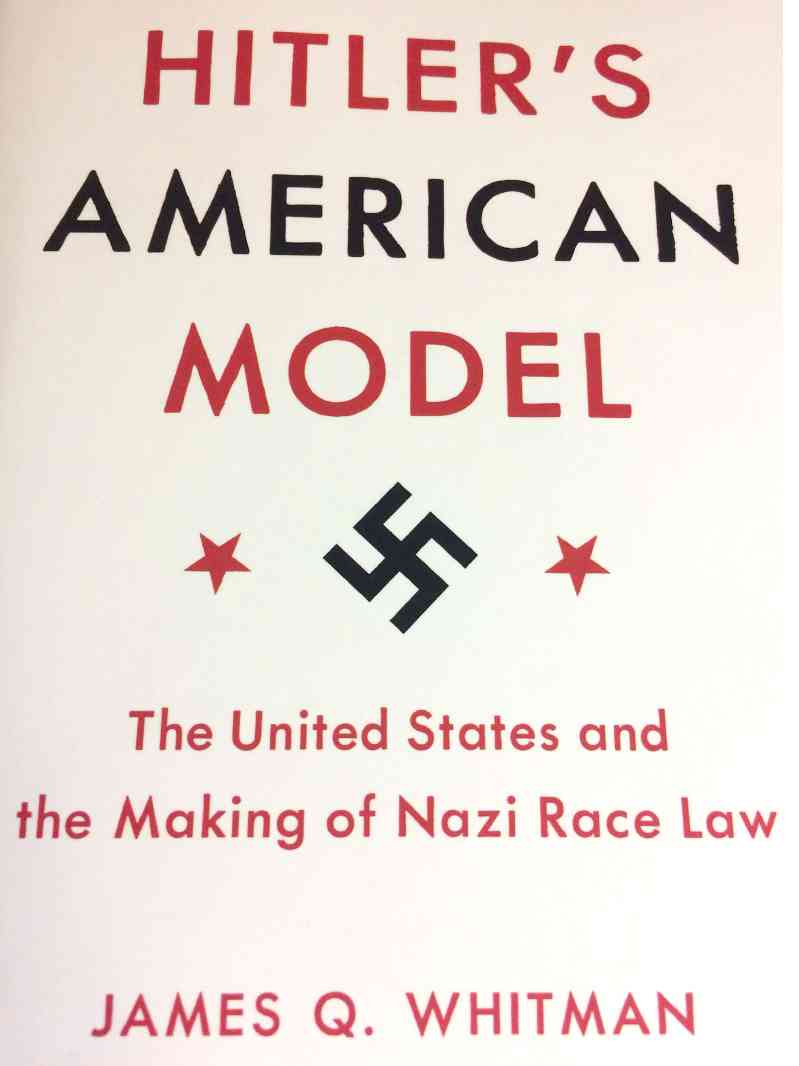

One model that Nazi Germany wanted to emulate was that of racist US laws enforcing segregation and prohibiting ‘miscegenation’ (inter-racial relationships). In 1934, leading Nazi lawyers met to draft the anti-Jewish ‘Nuremberg Laws’, and took for their model the notorious racist ‘Jim Crow’ laws of the USA. Anti-miscegenation laws that criminalized inter-racial sexual relationships and marriage were declared unconstitutional by the US Supreme Court as late as 1967. Hitler and the Nazis also admired another aspect of US racism – eugenics (forced sterilisation to prevent the birth of humans of genes deemed to be ‘inferior’). In the US in the 1930s, there were laws allowing forced sterilization of women deemed to be genetically ‘immoral,’ ‘criminal’ or disabled. A large proportion of such women were poor and/or Black. Hitler’s eugenics program (that finally led to genocide in the gas chambers) was also inspired by these racist laws.

Hitler also admired the genocide of the American Indians – the original inhabitants of the land now known as ‘USA’. “Indeed as early as 1928, Hitler was speechifying admiringly about the way Americans had “gunned down the millions of Redskins to a few hundred thousand, and now keep the modest remnant under observation in a cage.” (Hitler’s American Model, The United States and the Making of Nazi Race Law, James Q. Whitman, Princeton University Press, 2017)

In the era of the ‘Jim Crow’ laws, Black men in the US could be killed for having or even being suspected of having consensual relationships with white women. Mob lynching of Black men – often on the pretext of allegations of ‘raping’ white women – was common. We have seen how Nazi Germany admired and wanted to replicate racist laws that provided a pretext and a rationalization of such mob lynchings.

In India, too, we can easily see how the ‘love jehad’ bogey raised by the Sangh Parivar and its various outfits is a copy of the ‘Jim Crow’ and the Nazi models. These outfits make no secret of their hatred for the Indian Constitution that allows inter-caste and inter-faith marriage. In the name of combating ‘love jehad’, they justify violence against relationships and marriages between Muslim men and Hindu women.

Nazification of Media, Education and Culture

Goebbels had already brought about a thorough shake-up in German radio, now a good many newspapers were simply banned and others subjected to strict government monitoring and economic pressure. Some of the larger liberal newspapers were granted a measure of freedom, but even these were constrained by daily governmental press instructions and self-censorship.

Goebbels had already brought about a thorough shake-up in German radio, now a good many newspapers were simply banned and others subjected to strict government monitoring and economic pressure. Some of the larger liberal newspapers were granted a measure of freedom, but even these were constrained by daily governmental press instructions and self-censorship.

In the realms of music, film, theatre, the visual arts and literature, the process of Nazification ran parallel to the removal of Jews from of cultural life. Jewish artists and intellectuals had always been hated by the Nazis for their modernism and intellectual/cultural accomplishments and defamed as advocates of “cultural Bolshevism”; now they were completely ostracised. Not just because they were Jews but because many of them represented the rationalism, scientific spirit, artistic creativity and freethinking of which the Nazis were mortally scared. Why else should the 20th-century inquisitors organise book-burnings – where the best of German literature and those of other nations were committed to the flames -- in university campuses and elsewhere all over the country?

The bonfires organised by the students were in most cases supported by university authorities. The latter also helped the government cleanse the campuses of ‘undesirable elements’; the few who resisted were unceremoniously thrown out. Thanks to this atmosphere of savage intolerance, the very first year of the Nazi regime saw a mass exodus of artists, writers, scientists and journalists. Such outstanding members of the German intelligentsia and exponents of German culture as Einstein, L. Feuchtwanger, T. Mann, A. Zweig and many others were compelled to leave the country.

The establishment of the Reich Cultural Chamber, which was inaugurated with Hitler in attendance at the Berlin Philharmonic Concert Hall in November 1933, completed the reshaping of the entire arena of German culture. Anyone who wanted to work in film, music, theatre, journalism, radio, literature or the visual arts was required to be a member of one of the seven chambers that comprised this institution.

30 June 1934: “Night of the Long Knives”

The first major Nazi massacre was directed against its own people – the SA. And the reason was entirely political.

The first major Nazi massacre was directed against its own people – the SA. And the reason was entirely political.

When the Nazi party consolidated its power with the Enabling Act, the SA found itself robbed of their most important raison d’être: terrorising and neutralising the Nazis’ political opponents. Indeed, the Brownshirts’ violent activism had become superfluous and politically counter-productive. So in early August 1933 the government rescinded the decree which had made the SA an auxiliary police force. The consequent disgruntlement among SA men was accompanied by disillusionment among sections of the population triggered by price hike and stagnant wages, corruption and nepotism, unrealistic expectations from the Messiah remaining unfulfilled, and so on. Hitler was still very popular, but not all his colleagues. A report compiled by the SPD in exile based on information from sources within Germany, recorded as typical the sentiments of a Munich resident: “Our Adolf is all right, but those around him are all complete scoundrels.”

When the Nazi party consolidated its power with the Enabling Act, the SA found itself robbed of their most important raison d’être: terrorising and neutralising the Nazis’ political opponents. Indeed, the Brownshirts’ violent activism had become superfluous and politically counter-productive. So in early August 1933 the government rescinded the decree which had made the SA an auxiliary police force. The consequent disgruntlement among SA men was accompanied by disillusionment among sections of the population triggered by price hike and stagnant wages, corruption and nepotism, unrealistic expectations from the Messiah remaining unfulfilled, and so on. Hitler was still very popular, but not all his colleagues. A report compiled by the SPD in exile based on information from sources within Germany, recorded as typical the sentiments of a Munich resident: “Our Adolf is all right, but those around him are all complete scoundrels.”

The Regime

(excerpt)

A foreigner, returning from a trip to the Third Reich

When asked who really ruled there, answered:

Fear.

Fear rules not only those who are ruled, but

The rulers too.

Why do they fear the open word?

Given the immense power of the regime

Its camps and torture cellars

Its well-fed policemen

Its intimidated or corrupt judges

Its card indexes and lists of suspected persons

Which fill whole buildings to the roof

One would think they wouldn’t have to

Fear an open word from a simple man.

But their Third Reich recalls

The house of Tar, the Assyrian, that mighty fortress

Which, according to the legend, could not be taken by any

army, but

When one single, distinct word was spoken inside it,

Fell to dust.

Bertolt Brecht

The conjunction of popular discontent, still at a primary level though, with the palpable disquiet among the Brownshirts worried the ruling party bosses. They were especially perturbed when SA Chief of Staff Ernst Röhm referred to the popular dismay in an article published in June 1933 and observed that the “national uprising” had thus far “only travelled part of the way up the path of German revolution.” The SA, he asserted, “would not tolerate the German revolution falling asleep or being betrayed by non-fighters halfway towards its goal.” He made it clear that the SA did not want to be reduced to a mere recipient of commands from the party leadership. On the contrary, he laid claim to a position of power for himself and his organisation within the Third Reich. Röhm envisioned transforming the SA into a kind of militia army, thereby challenging the regular army’s monopoly on the right to wield weapons.

This was just too much for both the Nazi party and the military. After collecting incriminating material against the leaders of the SA and making necessary organisational preparations on the sly, Hitler decided on a double blow – against SA leaders and also against his old rivals such as Papen (who had in the meantime openly criticised the cult of personality surrounding Hitler and excessive violence).

The blow was handed out on the night of 30 June and over the next two days in what came to be known as the “Night of the Long Knives”. Hitler personally led the surprise campaign with SS men headed by Heinrich Himmler. Papen was allowed to escape death but placed under house arrest, Strasser and Röhm were murdered, about 180 SA men (thirteen of them were Reichstag deputies) killed and hundreds arrested.

Hitler was quick to get the cabinet approve a draft law that would legalise the series of murders ex post facto: “The measures taken on 30 June and 1 and 2 July to put down treasonous acts against the nation and states are a legal form of emergency government defence.”

The Burning of the Books

When the Regime

commanded the unlawful books to be burned,

teams of dull oxen hauled huge cartloads to the bonfires.

Then a banished writer, one of the best,

scanning the list of excommunicated texts,

became enraged — he’d been excluded!

He rushed to his desk, full of contemptuous wrath,

to write fiery letters to the morons in power —

Burn me! he wrote with his blazing pen

Haven’t I always reported the truth?

Now here you are, treating me like a liar!

Burn me!

Bertolt Brecht

(translation by Michael R. Burch)

“Führer and Reich chancellor”

A fortnight later, Hitler defended his unlawful action adamantly and eloquently in the Reichstag, invoking once again “the nation” and “the people”: “Mutinies are broken according to never changing laws. If someone tries to criticise me for not enlisting the regular courts, I can only say: in that hour, I was responsible for the fate of the German nation and was therefore the supreme judge of the German people.”

On 1 August, with Hindenburg on his death-bed, Hitler got a law to merge the offices of Reich president and chancellor and transfer the powers of the former to the “Führer and Reich chancellor,” approved by the docile cabinet. The old man died the next day and on 17 August the law was overwhelmingly confirmed in a plebiscite.

"Where they burn books, they will, in the end, also burn people.”

On the night of 10 May 1933, a crowd of some 40,000 people gathered in the Opernplatz – now the Bebelplatz – in the Mitte district of Berlin. Amid much joyous singing, band-playing and chanting of oaths and incantations, they watched soldiers and police from the SS, brownshirted members of the paramilitary SA, and impassioned youths from the German Student Association and Hitler Youth Movement burn, at the behest of propaganda minister Joseph Goebbels, upwards of 25,000 books decreed to be "un-German”….

The volumes consigned to the flames in Berlin, and more than 30 other university towns around the country on that and following nights, included works by more than 75 German and foreign authors, among them (to cite but a few) Walter Benjamin, Bertolt Brecht, Albert Einstein, Friedrich Engels, Sigmund Freud, André Gide, Ernest Hemingway, Franz Kafka, Lenin, Jack London, Heinrich, Klaus and Thomas Mann, Ludwig Marcuse, Karl Marx, John Dos Passos, Arthur Schnitzler, Leon Trotsky, HG Wells, Émile Zola and Stefan Zweig. Also among the authors whose books were burned that night was the great 19th-century German poet Heinrich Heine, who barely a century earlier, in 1821, had written in his play Almansor the words: "Dort, wo man Bücher verbrennt, verbrennt man am Ende auch Menschen" – "Where they burn books, they will, in the end, also burn people.”

- Jon Henley, ‘Book Burning: Fanning The Flames Of Hatred’, 10 Sept 2010, The Guardian

Having apparently eliminated all potential sources of conflict and opposition, and with no one to share power with, the Great Dictator was now free to prepare for leading the “master race” in a conquest of the world.

Note:

1. Institutions created around 1900 by the SDP to be used for social gatherings and political discussions and schooling of workers. They functioned as centres of the trade union movement.