Operation SAP I: Free Market Farces

CORNERED BY the scandalous revelations from Bombay, the government is now trying to put up a brave front. We are being told that it was a case of “systems failure and irregularities” with “evidence of collusion on the part of some bank officials” and that, in fact, “No official, big or small, is going to be spared”. The question, however, is not just of punishing Harshad Mehta or a few officials, howsoever big. For the BSE scam is no aberration. It epitomises the essential falsity and fraudulence of the new economic policy itself which through clever propaganda has glamourised our abject external dependence as the ultimate status symbol. The illusory euphoria of the stockmarket and the hard economic reality of all-pervasive stagnation are but two sides of the same coin. Now a look at the other face of the reforms.

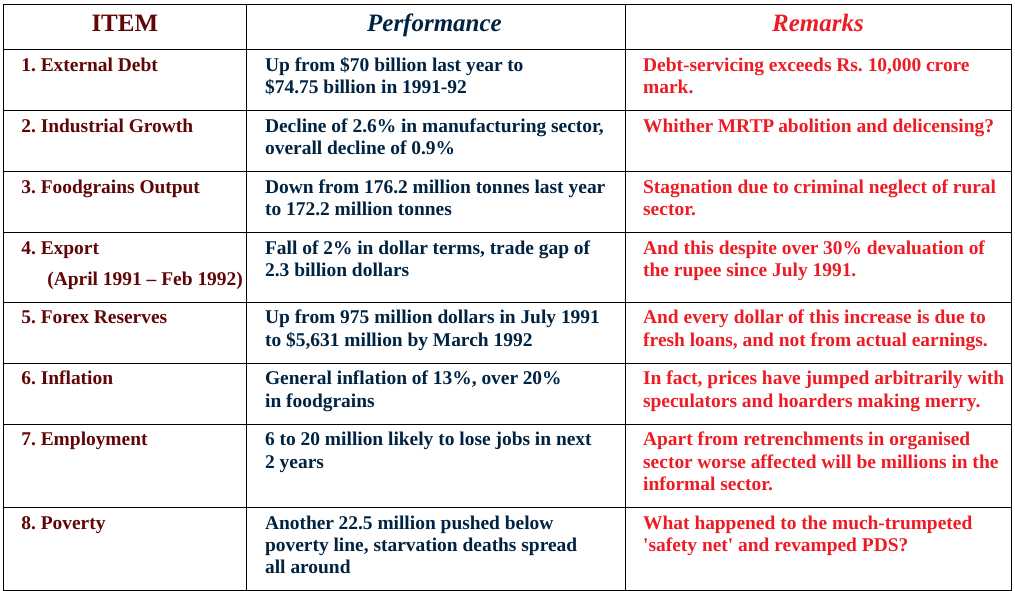

Economic Growth: The GDP growth rate has come down to 2.5% as against the average growth rate of 5.6% in the previous 11 years. For the first time in last ten years, industrial output registered an absolute decline of 0.9% between April and December 1991. The decline was sharpest in the manufacturing sector – over 2.6% – while that in mining was 0.6%. Production of foodgrains also fell from 176.2 million tonnes last year to 172 million tonnes, a shortfall of 10 million tonnes from the year's targeted output. The government would have us believe that the whole thing is a temporary problem, caused by a difficult foreign exchange position and consequent restrictions on imports. But in reality, the steady scaling down of public investment and the entire planning process has taken a heavy toll of the infrastructural sector, particularly in core areas like power, transport, shipping and telecommunication, cutting at the very roots of our economic base. The fall in agricultural output has also taken place in a year of normal monsoon which can only signify the setting in of a long-term stagnation.

Prices: The promise was to roll back prices of essential commodities within 100 days of Congress(I)'s return to power. Prices have instead kept soaring higher and higher. The official rate of inflation hovers around 13%, while for the common consumer at the retail market prices are going up at anything above 20%. And no group of commodities is exempt from this inflationary onslaught. With the government trying to reduce deficit by enforcing an across-the-board rise in excise duties, jacking up issue prices of foodgrains and administered prices of all infrastructural goods and services and slashing subsidies and imports being rendered costlier through devaluation and partial convertibility of the rupee, there seems no escape from the clutches of runaway inflation.

Job Opportunities: According to a Planning Commission estimate, 3.5 million job opportunities were lost in the first year of the programme. As a result, the backlog of open unemployment (the shortfall in generation of new employment opportunities) has increased to 17 million jobs this year from about 13 million last year. In addition, the threat of joblessness looms large over nearly a million workers in sick units. According to independent estimates the structural adjustment programme will result in the unemployment of four to eight million people in 1992-93 and four to ten million more in 1993-94. Experts also warn that the increase in unemployment will be particularly felt in the informal sectors while in the organised industrial sector, there will be increasing casualisation of labour.

Poverty: A study by the pro-reform Indian Council for Research in International Economic Relations has revealed that in the first year of structural adjustment, another 22.5 million additional persons were pushed down the poverty line. With rise in foodgrain prices and reduction in food subsidy, the public distribution system (PDS) has been pushed to the brink of breakdown. The revamped PDS campaign launched in January this year covering some 1,700 remote rural blocks will remain a hoax unless prices are brought down and supplies increased. The phenomenon of starvation deaths is no longer confined to drought-hit Kalahandi. Hunger-related deaths are now as common among weavers in Andhra Pradesh and sick industry workers in West Bengal as among toiling tribal masses in Orissa and Madhya Pradesh, Tripura and Maharashtra.

Exports: Between April 1991 and February 1992, exports in dollar terms fell by 2%. The disintegration of the Soviet Union and the traumatic transition of Eastern Europe from the Soviet camp to market-friendly global capitalism have caused big jolts to Indian foreign trade. The prospect of enhancing exports to the recession-ridden industrial economies of the western world too remains quite bleak. And if the Dunkel proposals and penal duties imposed on Indian drug exports to the US under the Special 301 provision are any indication, Indian exporters will continue to face an extremely rough weather in the global market, and all this despite devaluation and faithful adherence to the Fund-Bank prescriptions.

FOREX Reserves: The foreign exchange position of the country is of course no longer as precarious as it had been a year ago. From a bare 975 million dollars in July 1991, the reserves reached a rather comfortable 5,631 million dollars by March 1992. But this recovery is however not due to any upswing in export performance or any narrowing down of the trade gap, which stands at a staggering 2.3 billion dollars. Apart from last year's import curb measures, the improvement can only be explained in terms of high-cost, high-conditionality fresh borrowings contracted from IMF and other sources. The debt-burden has consequently shot up to a phenomenal 74.75 billion dollars, i.e., Rs. 2,25,000 crore, while our annual debt-servicing obligation has exceeded the alarming Rs. 10,000 crore mark.

Report Card of Reforms