Dollar-Rupaiya, Bhaiya-Bhaiya?

NOW LFT us note some of the major political implications and lessons of the new economic regime. Firstly, the changes in economic policy are supplemented by a matching shift in foreign policy. Rarely in the four decades of Indian Independence has our foreign policy been marked by such a blatant pro-Americanism stretching from India's blanket support to US positions and actions on every international controversy to joint naval exercises on Indian Ocean. The traditional rhetoric of “non-alignment” and “South-South cooperation” is being increasingly replaced by the phraseology of “global integration” and “North-South interdependence”. And as far as the ruling classes are concerned, this transition from “Nehruvian socialism” to market-friendly capitalism has been nothing more than shedding a long worn-out mask.

Admirers of Nehru in the Left may still feel haunted by the nostalgic memories of his alleged 'socialist, anti-monopoly economic orientation' and 'anti-imperialist' non-aligned foreign policy of the Nehru-Indira era, but barring a few discordant notes here and there, there has been no serious dissension within the Congress over the new policies. In fact, the new policies have also added a new dimension of collaboration to the traditional rivalry between the two main parties of the Indian Right, the Congress and the BJP. Any effective opposition to the new policies must also be able to counter this unity and consolidation of the Indian Right with a matching unity of purpose and action on the part of the Indian Left.

Secondly, while it is true that the Indian ruling classes have to come to terms with a growing neo-colonial offensive, we must not take a simplistic view of the whole situation. The new economic policy is not just something imposed by the IMF-World Bank lobby on a reluctant Indian ruling elite, it is more of a joint venture of the Indian rulers and their imperialist partners. Naturally, while the formulation and execution of the new policies are marked overwhelmingly by concurrence and collusion between the two, conflicts and frictions, though of secondary importance, are also integral features of this collaboration. The whole argument of the neo-swadeshi advocates pitting 'Indian' goods and industry against goods produced by Indian subsidiaries of foreign multinationals negates this complex integral relation and assumes a simple and false dichotomy between Indian big business and their foreign collaborators.

We must remember that even though the new economic and foreign policies have taken a heavy toll of our limited bargaining strength in the global economy, it is perfectly possible that on specific issues of the new package some Rightwing leaders or maybe even the government itself adopt an oppositional stand. But that does not mean that we should single out the foreign aspect of the new economic design and run after a broad-based all-party national opposition to the neo-colonial offensive. The time has come to reject the old false and self-defeating concept of patriotism or swadeshi which fights foreign capital only to sacrifice the working people at the altar of its Indian counter part. Today's new patriotism must establish-the paramountcy of the well being of working India. Instead of denouncing foreign capital in the abstract it must take on the integrated Rupee-Dollar nexus.

And last but not the least, there is the question of providing an alternative economic policy. The biggest argument of Narsimha Rao is his plea of 'helplessness': there is no other alternative, IMF is the only option and naturally we will have to comply with some of its conditionalities, of course, only in our best national interest! Obviously, just as the old model of command economy and state socialism has proved incapable of standing up to the latest challenges of world capitalism, in India we cannot fall back upon the old slogans and practice of planning, public sector and self-reliance to resist the Fund-Bank model. Economic modernisation and a drastic overhauling of the public sector are clearly an urgent agenda of reform that no one can ignore.

But our experience with ten years of economic liberalisation and especially with last one year's structural adjustment programme shows equally clearly that on the existing institutional basis no amount of reforms can convert India into a real economic success-story. It can only give us more foreign debt and financial scandals. These days, it has become fashionable among Indian policy-makers to cite the growth experience of the newly industrialised smaller Asian economies like South Korea, Taiwan, Malaysia, Thailand and even port-states like Singapore and Hong Kong! The comparison is misplaced on more counts than one – firstly, India is too big, too complex and too different from these countries, and secondly, even in a country like South Korea, the reforms have been implemented in a much more selective way and on a much more sound infrastructural footing.

The bankruptcy of our new economic policy is best exposed when we compare our economy with China's, the only real comparable experience. The more our policy-makers try and justify the reforms here by drawing parallels with the Chinese reforms, which appear not only similar but even much bolder at times, the more the Chinese experience stands apart by virtue of its incomparably superior results (see box). Evidently, while China with her sound economic infrastructure and a much more modern and developed institutional framework has found her own suitable course of reforms, we are still a hostage to our colonial legacy, looking for prosperity through blind imitation of others' experiences and faithful implementation of Fund-Bank prescriptions.

The fight against the new economic policy is ultimately a struggle for an economic road suited best to our specific conditions and national interests. And whatever mode of transport we may take, the following direction is a must – radical agrarian reforms as the key to all economic development and modernisation; revamping of state sector in core areas with particular emphasis on democratic management; decentralisation of ownership in industry; incentive to native entrepreneurship; and top priority to investment in people with emphasis on development of skills and democratisation of social life. Any other path, however glamorous, can only lead to the dead end of endless dependence.

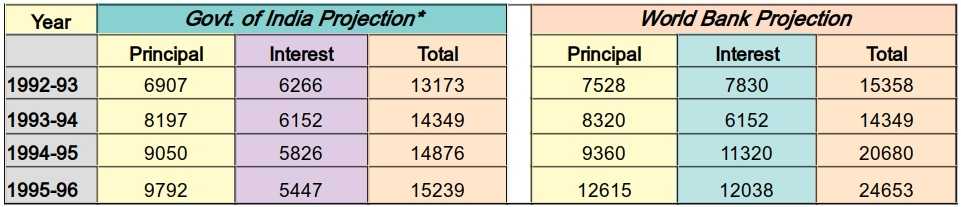

India's Debt-Servicing Burden

(In Rs. Crore, calculated on the basis of Rupee-Dollar Exchange Rate in the wake of July 1991 Devaluation)

* = cited in CAG Report, 1992, on Union Govt., Account

Chinese Economy

Neighbour's Envy, Owner's Pride!

AS Indian policy makers go hunting around the globe in their quest tor free market models to ape, right at their doorstep an economic miracle awakens. Putting the market mechanism and material incentives to creative use, Socialist China is an example of what rapid growth can really mean given the right socio-economic base and leadership. Conner the fads:

During the Eighties, China- Doubled her per capita income,

- More than doubled her GNP,

- Trebled exports from $ 18.1 billion to $ 62.1 billion,

- Increased foodgrain output from 300 million tonnes to 435 million tonnes,

- Raised production of steel from 37.12 million to 66.04 million tonnes, coal from 620 to 1,080 million tonnes, and cement from 80 to 203 million tonnes,

- Increased generation of electricity from 300 to 618 billion kwh and crude oil production from 106 to 138 million tonnes.

Today China is the world's fourth largest producer of steel, chemical fibre and non-ferrous metals. It is also the single largest producer of foodgrains, cotton, meat, textiles, cement and machine tools. And all this was achieved while keeping the inflation rate down to a little over 1 per cent till the end of the decade.

The rapid expansion of exports has been achieved through a qualitative change in its entire export structure with manufactured goods now accounting for 70%, of this capital goods alone form 34%, the rest being readymade garments, consumer electronics, telecommunication equipments, toys and machinery.

Among the developing nations, today China has the most comfortable indebtedness position with external debt standing at 43.9 billion dollars and with a debt-servicing ratio of just 9%.

The transformation has been most momentous in the Chinese countryside where small and medium entreprises have sprung up by the millions providing employment and checking migration to urban areas. In 1989 these entreprises exported over 10 billion dollars worth of goods and services.

While these dramatic developments have not been without negative social fallout like the weakening of social welfare measures and growing commercialisation of life the lessons for a country like India are obvious. First get rid of all medieval vestiges, carry out land reforms, develop the skills of the masses and then aspire for the moon.