Ranveer Sena: Fascist, Feudal, Communal Militia

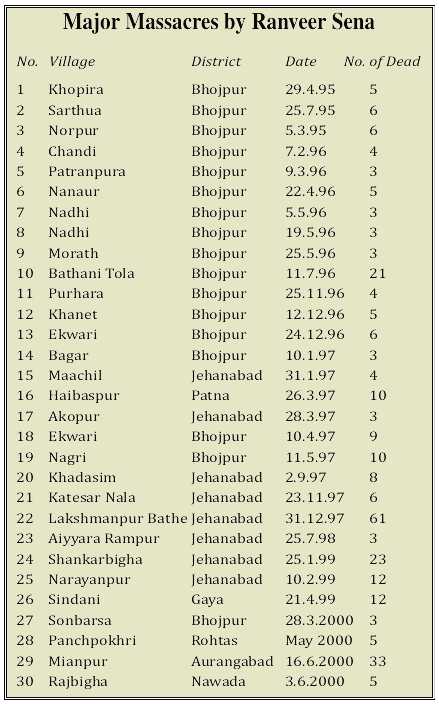

MASSACRES of dalit rural labourers by dominant-caste armies were nothing new in Bihar. But in its sheer scale and ferocity, the Bathani Tola massacre marked a new phase and signified a new reactionary political mobilisation. The Ranveer Sena comprised of predominantly Bhumihar landed gentry but using the bond of caste and the shared social bias against the downtrodden, Ranveer Sena was able to sway large sections of Bhumihar peasantry as well as a section of Rajput landed gentry. The Sena had deep ideological and political linkages with the Sangh Parivar and BJP, apart from enjoying the patronage of Bhumihar-Rajput politicians from across the spectrum of ruling class parties. And their specific objective was to unleash terror, to suppress the growing mobilisation of agricultural labourers and poor peasants on socio-economic issues, and their political assertion, especially under the banner of the CPI(ML) Liberation.

One key context for the rise of the Ranveer Sena – and for the Bathani Tola massacre – was the victory of CPI(ML) in the Assembly seats of Sahar and Sandesh in Bhojpur in 1995. It was this political assertion that was the catalyst for the formation and virulent feudal reaction of the Ranveer Sena. This political victory came as a culmination of the material and political challenges posed by the landless poor (overwhelmingly of oppressed castes) against the feudal hierarchical order of caste and class, and their political representatives.

At Bathani Tola, one woman was gang-raped before being killed. Another’s breasts were chopped off. A baby girl was tossed in the air and slashed with a sword as she fell. One 10-year-old girl’s arms were shopped with a sword. Small boys lost their lives due to terrible sword injuries. Homes where people were sheltering were set on fire. Such acts by the Ranveer Sena appear to have provided a sort of template for some of the horrors of the Gujarat massacre by the Sangh Parivar.

Bathani Tola’s landless poor dalits and minorities were being punished for the temerity of their political and social assertion with the CPI(ML). After Bathani Tola, other large-scale massacres at Laxmanpur Bathe, Shankarbigha, Narayanpur and Miyanpur followed, targeting variously the social base of the CPI(ML), the COC(Party Unity) faction which has now merged with the Maoists, and even poor Yadavs who were the social base of the RJD.In the wake of the massacres at Bathani Tola and Bathe, there was a persistent discourse that ruling class parties, the mainstream media, and even the social democratic Left, sought to peddle. This discourse downplayed the massacres, speaking of them as part of a supposed ‘war of attrition’ or ‘caste war’ between the Naxalites and the Ranveer Sena. The struggles of the poor peasants and labourers for increased wages, land, and dignity were deemed to be a ‘provocation’ – and the Ranveer Sena rationalised as a natural response to such provocation. The CPI(ML) was accused of pitting agricultural labourers against peasants, and the Ranveer Sena posed as the representative of ‘peasants.’ In his press conference following the acquittal, Brahmeshwar Singh has again spoken of how some forces are seeking to break the ‘unity’ of peasants and agricultural labourers.

The myth that the struggle between Ranveer Sena and CPI(ML) was a ‘caste war’ is exposed totally by what a Ranveer Sena sympathiser told the correspondent of The Hindu, after the acquittal. Justifying the massacre as a “reactionary mobilisation” of the upper castes against “those Naxals,” the Ranveer Sena sympathiser declared, “The land is ours. The crops belong to us. They [the labourers] did not want to work, and moreover, hampered our efforts by burning our machines and imposing economic blockades. So, they had it coming.” The very fact that those who had been oppressed for centuries, were having the temerity to organise and assert themselves socially, economically, and politically, was enough to merit being massacred.

A booklet issued by the CPI(ML) (Yeh Jang Zarur Jiten, 2000) pointed out that by calling landlords and even big grain traders ‘peasants,’ and calling for unity of agricultural labourers with these ‘peasants,’ the Ranveer Sena and its apologists, as well as the ruling class parties, were actually rationalising oppressive class and caste hierarchies and atrocities. As long as agricultural labourers were willing to remain subordinate to the landlords, there would be ‘peace’, but as soon as they assert their independent identity and demand rights and dignity, they would be met with the full ferocity of feudal reaction.

The booklet recalled that Swami Sahajanand Saraswati, the Kisan Sabha founder whose legacy the Ranveer Sena was trying to appropriate, had written a book called ‘Khet Mazdoor’ (Agricultural Labourer) while in Hazaribagh Jail in 1943. While advising against an agricultural labourers’ organisation separate from the Kisan Sabha, Swami Sahajanand had emphasised that the Kisan Sabha must keep agricultural labourers at its core. In his words, “Agricultural labourers are the soul of agriculture.” Brahmeshwar Singh’s ‘kisans’ (‘peasants’) are those who massacre the ‘soul of agriculture’ – i.e the poor peasant and farm labourer. The Ranveer Sena is nothing but a private army of landlords and big traders: having nothing remotely in common with peasants.