Workers And Peasants In India's Freedom Struggle

[Excerpts from India's March to Freedom: The Other Dimension by Dipankar Bhattacharya, a booklet published by Liberation Publications in July 1997 to mark the 50th anniversary of Indian independence.]

Peasant Upsurges and Tribal Revolts

Peasant rebellions and tribal revolts were the two main, often overlapping, expressions of resistance against British rule in the 18th and 19th centuries. Anthropologist Kathleen Gough has compiled a list of no less than 77 peasant uprisings during the British period.

rebellion by The Illustrated London News.

WIKIMEDIA COMMONS

The Sannyasi Rebellion that shook vast areas in Bengal and Bihar in the second half of eighteenth century was one of the earliest instances of peasant resistance against British rule. The introduction of Permanent Settlement saw the flame of peasant rebellion engulf the southern region of Tamil Nadu. Palayankottai near Tirunelveli was the epicentre of this massive upsurge led by Veerapandaya Kattabomman. Kattabomman questioned the very legitimacy of British tax claims: “The sky gives us water and land gives us crops, why should we then pay taxes to you?” The Wababi Uprising in Bengal led by Titu Meer and his peasant followers in early 1830s combined aspects of religious reform and peasant insurgency. On the eve of the First War of Independence in 1857, the Birbhum-Rajmahal-Bhagalpur section of the Bihar-Bengal border region witnessed the great Santhal Uprising against the extortionist alliance of the police, landlords, moneylenders and court officials. The names of Sidho and Kano, the legendary heroes of this uprising, as also of Baba Tilka Manjhi who led an earlier phase of Santhal rebellion in 1784-85, are still widely remembered in Eastern India.

Recent researches have also established the fact that the First War of Independence in 1857 had an unmistakably pronounced peasant content. British colonialism went on to win this war and consolidate its grip over India, but the fire of peasant insurgency and tribal revolts continued to simmer over large parts of the country. Between 1836 and 1919, the Malabar region of Kerala recorded 28 outbreaks of Moplah Rebellion. Despite misleading religious overtones, it was essentially a revolt of Muslim leaseholders and landless labourers against Hindu upper caste landlords and their British benefactors. In 1860s Bengal witnessed the popular Indigo Rebellion, peasants rebelling against the forcible introduction of indigo cultivation by British planters.

An Everlasting Disgrace

This is indeed a pretty state of things in a civilized army in the nineteenth century; and if any other troops had committed one-tenth of these excesses how would the indignant British press brand them with infamy. But these are the deeds of the British army, and therefore we are told that such things are but the normal consequences of war. ... The feet is, there is no army in Europe or America with so much brutality as the British. Plundering, violence, massacre – things that everywhere else are strictly and completely banished — are a time-honoured privilege, a vested right of the British soldier. ... For twelve days and nights there was no British army at Lucknow – nothing but a lawless, drunken, brutal rabble, dissolved into bands of robbers far more lawless, violent and greedy than the sepoys who had just been driven out of the place. The sack of Lucknow in 1858 will remain an everlasting disgrace to the British military service.

— Engels on the role of the British army in India in 1857

The hills of the Godavari Agency region in Andhra also reverberated to repeated outbursts of rebellion through the nineteenth century. The British-backed mansabdar’s attempt to enhance taxes led to the outbreak of a major revolt in March 1879 over an area as vast as 5,000 square miles and it could be suppressed by November 1880 only with the use of six regiments of Madras infantry. The transition from the nineteenth to the twentieth century was rocked by the legendary Ulgulan (Great Tumult) of Birsa Munda in the region south of Ranchi. At the heart of this great rebellion lay the popular tribal will to defend their traditional khuntkatti (joint holdings) rights and reject the imposition of beth begari (forced labour) by alien landlords.

It is true that most of these early peasant upsurges and tribal revolts were localised or at best regional affairs and not all-India campaigns. It is also true that these acts of rebellion were not propelled by any grand vision or conscious doctrine of a free and democratic modern India. Rather they were rooted in the appalling conditions of rural existence-persistence of famine or a near-famine situation, acute social oppression, feudal coercion and a reign of unmitigated loot and plunder by an alliance of powerful rural forces under the protective umbrella of British colonialism. No wonder, religious customs, tribal traditions and elements of caste, locality and a host of other pre-modern identities often overlapped and intermingled in these early expressions of popular unrest. Yet there was something very genuine and solid about these revolts, which stands out in sharp contrast to the politics of collaboration and measured opposition pursued by and large by the business and mercantile community as well as sections of the newly emerging middle class intelligentsia in the period which followed.

Arrival of the Indian Working Class

The first footsteps of the Indian working class could be heard in the second half of the nineteenth century. Facilitated by the introduction of railways in 1853, industries like cotton textile and jute as well as coal mining and tea plantation began to come up in different parts of the country. Early instances of workers trying to organise and revolt against their oppressive living and working conditions date back almost to the same period. Strikes of non-industrial workers like palanquin bearers and scavengers have also been recorded in the dosing years of nineteenth century.

Quite understandably, the formation of trade unions proper was preceded by the launching of various welfare organisations often by non-worker philanthropist citizens. At a time when the working class was still in its inception or infancy, with no tradition of trade unions or factory acts or labour laws, clear demarcation between various forms of organisation and categories of demands was often not possible. But given the fact that the mill managements were overwhelmingly white and the air was heavy with the humiliation and hatred generated by a racist, colonial order, even the most ordinary and primary attempts to organise the workers and articulate their demands tended to acquire an unmistakable political significance.

Swadeshi: The First Surge of Working Class Action

The first surge of working class action came in the wake of Partition of Bengal and the subsequent swadeshi agitation. On 19 July, 1905 Curzon issued his fiat partitioning Bengal. This sinister application of the British strategy of divide-and-rule in one of the most sensitive Indian provinces anticipated the eventual vivisection of the country in 1947. The Partition of Bengal provoked angry outbursts not only in Bengal itself but also in distant Maharashtra, a sure sign of the rise of a popular national consciousness.

In a two-pronged campaign, spearheaded primarily by the so-called extremist wing of the Indian National Congress led by Lala Lajpat Rai, Bal Gangadhar Tilak and Bipin Chandra Pal (the famous Lal-Bal-Pal trio), people were urged on the one hand to boycott British goods and promote Swadeshi ways on the other. Most of the Swadeshi leaders advocated the use of religious idioms to mobilise the masses. Tilak came up with the idea of celebrating Ganesh and Shivaji Utsavs.

This was also the formative phase for revolutionary terrorists. The attempt made by Khudiram Basu and Prafulla Chaki at Muzaffarpur on April 30, 1908, on the notorious British magistrate Kingsford was the most well-known terrorist action of this early period. But beyond this interface between religious revivalism and revolutionary terrorism, Swadeshi also had a distinct working class dimension.

Calcutta in Mourning

Yesterday was one of the most memorable days in the history of the British administration of India. It being the day on which the Bengal Partition scheme took effect, ... the people of Calcutta, irrespective of nationality, social position, creed and sex, observed it as a day of mourning ... From the small hours in the morning till noon, the bank of the Ganges from Bagbazar to Howrah presented a unique spectacle. It looked, as if it were, a surging sea of human faces. The scene in the roads and streets of Calcutta was quite novel and was perhaps never before witnessed in any Indian city. ... All the mills were closed and the mill hands paraded the city in procession. The only cry that was heard was that of Bande Mataram”.

- Amrita Bazar Patrika, Calcutta, 17 October, 1905

The first real trade union, the Printers’ Union, was formed on 21 October, 1905 in the midst of a stubborn strike in government presses. During July-September 1906, workers in the Bengal section of the East Indian Railway launched a series of strikes. On 27 August there was a massive assertion of workers at the Jamalpur railway workshop. The rail strikes would become more decisive and widespread between May and December 1907 covering important centres like Asansol, Mughalsarai, Allahabad, Kanpur and Ambala. Between 1905 and 1908, strikes were also quite frequent in the jute mills of Bengal. In March 1908, workers at the foreign-owned Coral Cotton Mills at Tuticorin in Tirunelveli district of the then Madras province went on a successful strike. Efforts to suppress the Coral mill workers led not only to protest strikes by municipal workers, sweepers and carriage-drivers, but municipal offices, law courts and police stations at Tirunelveli town too were attacked by the masses.

More importantly, Swadeshi signalled the arrival of the working class as a political force with workers beginning to take to the streets together with students and peasants demanding freedom and democracy. Militant street fights would soon become the order of the day. In the first week of May 1907, about 3,000 workers of the Rawalpindi workshop and hundreds of fellow workers from other factories joined the students in a huge protest demonstration against the conviction of the editor of the journal Punjabee for publishing ‘seditious’ matters. Peasants from nearby areas also joined this militant rally and virtually everything with a British connection came under attack.

Lenin Hails the Political Awakening of Indian Workers

Meanwhile the Russian revolution of 1905 had failed but not before it had inspired the entire international working class movement with a new vision and with a brand new weapon: the mass political strike. When Bipin Chandra Pal was arrested, the Calcutta journal Nabasakti wrote on 14 September, 1907: “The workers of Russia today are teaching the world the methods of effective protest in times of repression – will not Indian workers learn from them?”

This anticipation soon came true in Bombay. The arrest of Tilak on 24 June, 1908 provoked a storm of protest not only in Bombay but also in industrial centres like Nagpur and Sholapur. While court proceedings were on, workers would explode in protest and clashes would ensue with the police and military. In one of these street battles, on 18 July, several hundred workers were wounded and many killed. The next day some 65,000 workers belonging to 60-odd mills went on strike. Dock workers of Bombay also joined the movement on 21 July. On July 22, Tilak was sentenced to six years of rigorous imprisonment. In protest, for six days striking workers converted Bombay into a veritable battle field.

Lenin hailed this heroic assertion of Bombay workers as an inflammable material in world politics: “... in India the street is beginning to stand up for its writers and political leaders. The infamous sentence pronounced by the British jackals on the Indian democrat Tilak ... evoked street demonstrations and a strike in Bombay. In India, too, the proletariat has already developed to conscious political mass struggle — and, that being the case, the Russian-style British regime in India is doomed!”

The Swadeshi aftermath had already seen a significant upswing in revolutionary militancy in Bengal. The Yugantar and Anushilan groups emerged as the two key centres and in spite of the revocation of Partition in December 1911, the Bengal militants continued to gain in strength and popularity. The foremost leader of this school, Jatin Mukherjee (Bagha Jatin), died a hero’s death near Balasore on the Orissa coast in September 1915.

Revolutionary militancy also struck strong roots among Indian expatriates, mostly Sikhs, in British Columbia and United States. The famous Ghadr (revolution) movement began in 1913 in San Francisco. In contrast to the Hindu overtones of early Bengal militants, Ghadrites invoked the 1857 legacy of Hindu-Muslim unity. Many of the terrorists and Ghadrites were to be transformed eventually into communist activists.

With the outbreak of the First World War, British imperialists intensified their reign of repression in India. Even after the war was over, the British tried to perpetuate and legalise the war-time suspension of basic rights by pushing through the so-called Rowiatt Act, against which a popular offensive was soon unleashed by various sections of Indian people.

Brutal Repression and Upswing in Worker-Peasant Action

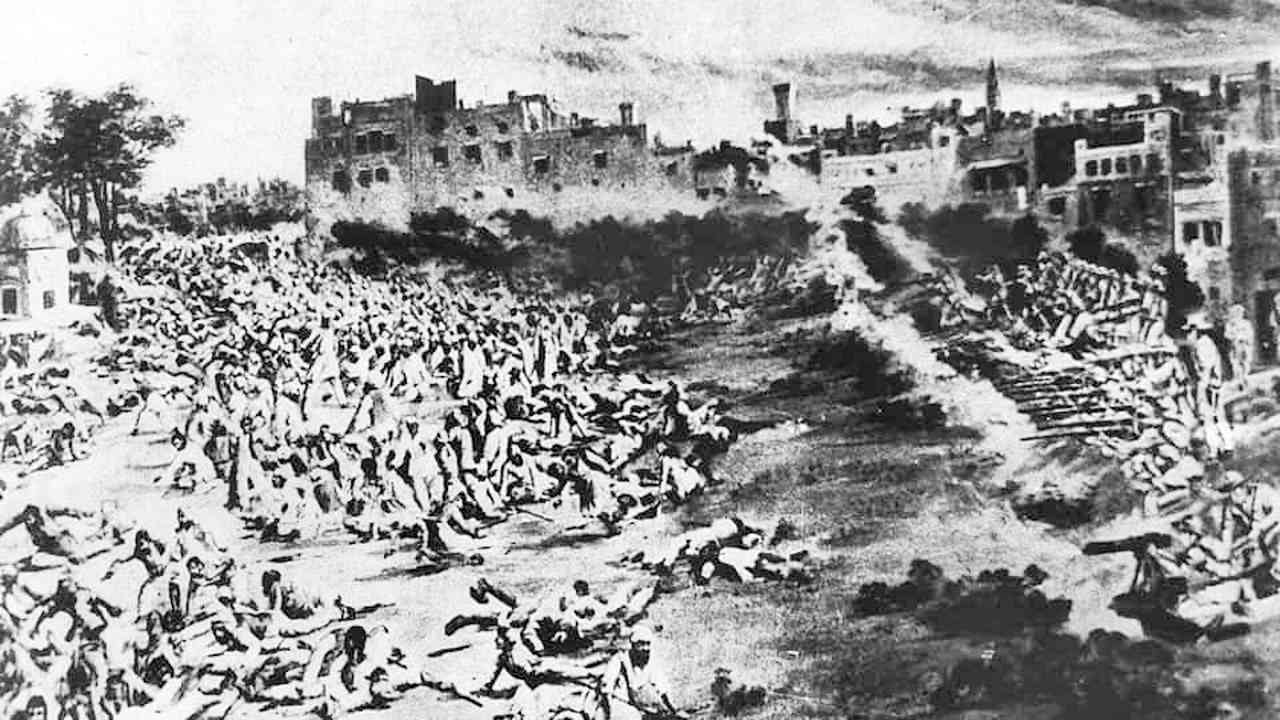

British colonialists tried their level best to crush the post-war popular upsurge through sheer repression. The worst instance of repression in this period was the barbaric Jallianwallahbagh massacre in Amritsar on 13 April, 1919. The infamous General Dyer who executed this massacre defended it in terms of “producing a moral effect” and his only regret was that had he not run out of ammunition he could have killed many more! In the face of such acute state terror and Gandhian vacillation and dilution, if the Indian people succeeded in producing a different ‘moral effect’ on the British administration, it was largely due to the powerful working class initiative and wider expressions of peasant discontent.

Thus Spake the Butcher

I fired and continued to fire till the crowd dispersed, and I considered that this is the Least amount of firing which would produce the necessary moral and widespread effect it was my duty to produce if I was to justify my action. If more troops had been at hand the casualties would have been greater in proportion. It was no longer a question of merely dispersing the crowds but one of producing a sufficient moral effect, from a military point of view, not only on those who were present, but more specially throughout the Punjab. There could be no question of undue severity....

— Gen. Dyer’s report to the General Staff Division, 25.08.1919

Tagore Renounces Knighthood in Protest

The disproportionate severity of the punishments inflicted upon the unfortunate people and the methods of carrying them out, we are convinced, are without parallel in the history of civilised governments. ... the very least that I can do for my country is to ... voice... the protest of the millions of my countrymen ... The time has come when the badges of honour make our shame gliding in their incongruous context of humiliation, and I for my part wish to stand shorn of all distinctions, by the side of those of my countrymen, who, for their so called insignificance, are liable to suffer a degradation not lit for human beings...

— Rabindranath Tagore’s letter to the Viceroy, 31.05.1919

Among the powerful peasant movements of this period, mention must be made of the popular peasant agitation in UP against the arbitrary rent collection and other coercive practices by the Avadh talukdars. This agitation which acquired a strong base in Pratapgarh, Rae Bareli, Sultanpur and Faizabad districts of UP was led by Baba Ramchandra; a one-time indentured labourer in Fiji who combined a lot of Ramayana with his calls of kisan solidarity and would even describe Lenin as the dear leader of kisans. In the Mewar region of Rajasthan, Motilal Tejawat organised a powerful movement of the Bhil tribe. In August 1921, the Malabar region of Kerala was rocked by a fresh round of the intermittent Moplah rebellion. In the early 1920s, Punjab saw a powerful upsurge of the Jat Sikh peasantry in the form of the Akali-led Gurudwara reform movement aimed at liberating the Sikh shrines from the clutches of corrupt British-backed mahants. And between 1919 and 1921, Satara district of Maharashtra witnessed a powerful anti-landlord anti-mahajan peasant upsurge led by the Satyashodhak Nana Patil who would go on to emerge as a popular communist peasant leader in the state.

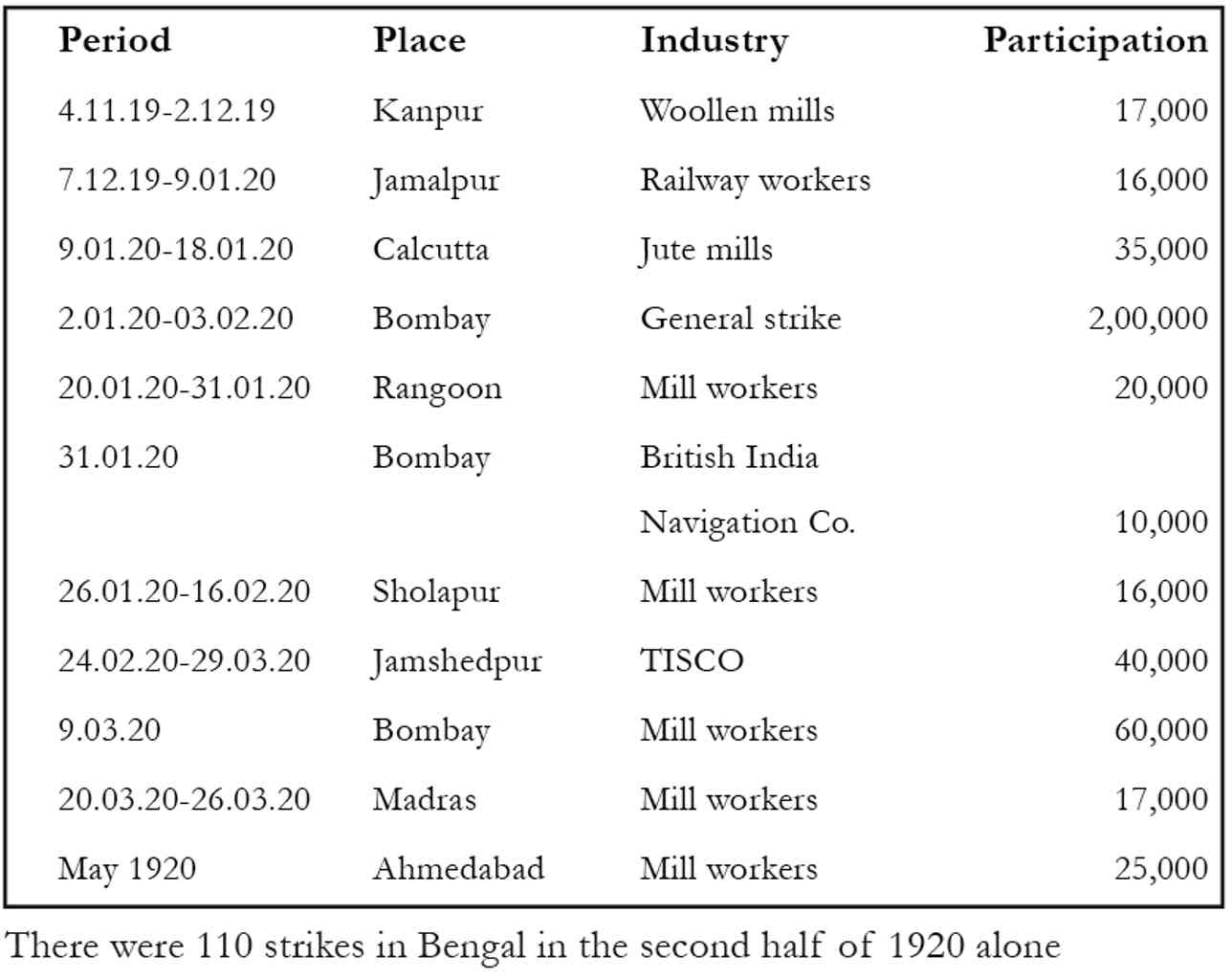

Parallel to the upswing in peasant movement, there was a strong strike wave sweeping across the country. The following figures quoted from a 1923 publication (cited by Sumit Sarkar in Modern India) give an idea about the depth and sweep of the strike-wave:

There were 110 strikes in Bengal in the second half of 1920 alone

Workers’ Organisation Acquires All India Shape

It was in the midst of such a powerful countrywide assertion of the working class that the first central organisation of Indian workers came into being. The All India Trade Union Congress was founded in Bombay on 31 October, 1920. Tilak was a key inspiration behind the birth of AITUC, but he expired on 1 August, 1920, three months before the actual inception of the organisation.

The inaugural session had all the fervour of a new-found proletarian identity, but ft could not move out of the Congress trajectory of constitutional reforms. In his presidential address, Lala Lajpat Rai emphasised the role of organised labour as the antidote against capitalism as well as “militarism and imperialism ... the twin children of capitalism” and underscored the need to “organise our workers (and) make them class conscious”; but with regard to the British government he said the attitude of labour should be “neither one of support nor that of opposition.”

The “Manifesto to the Workers of India” released on this occasion by the first General Secretary of AITUC, Dewan Chaman Lall, called upon the “Workers of India” to “assert your right as arbiters of your country’s destiny”. It reminded them that they must remain “part and parcel” of the movement for national freedom and urged them to “cast all weakness... and ... tread the path to power and freedom”. Vice-President Joseph Baptista, however, waxed eloquent about “the higher idea of partnership”, emphasising that mill-owners and labourers “are partners and co-workers and not buyers and sellers of labour”.

The second, conference of AITUC (30.11.1921 - 02.12.1921) held at the coal-town of Jharia in Dhanbad district of today’s Bihar (reckless and faulty mining by BCCL has unfortunately jeopardised the very existence of this historic working-class centre which also hosted the ninth AITUC session in December 1928 that called for transforming India into a Socialist Republic) was, however, much more emphatic about the goal of the Indian workers and the people at large. “The time has now arrived”, the conference declared, “for the attainment of swaraj by the people”. The Jharia session was an extraordinary event-some fifty thousand people, most of them coal miners and other workers from nearby areas and their family members, participated in this unprecedented show of worker power.

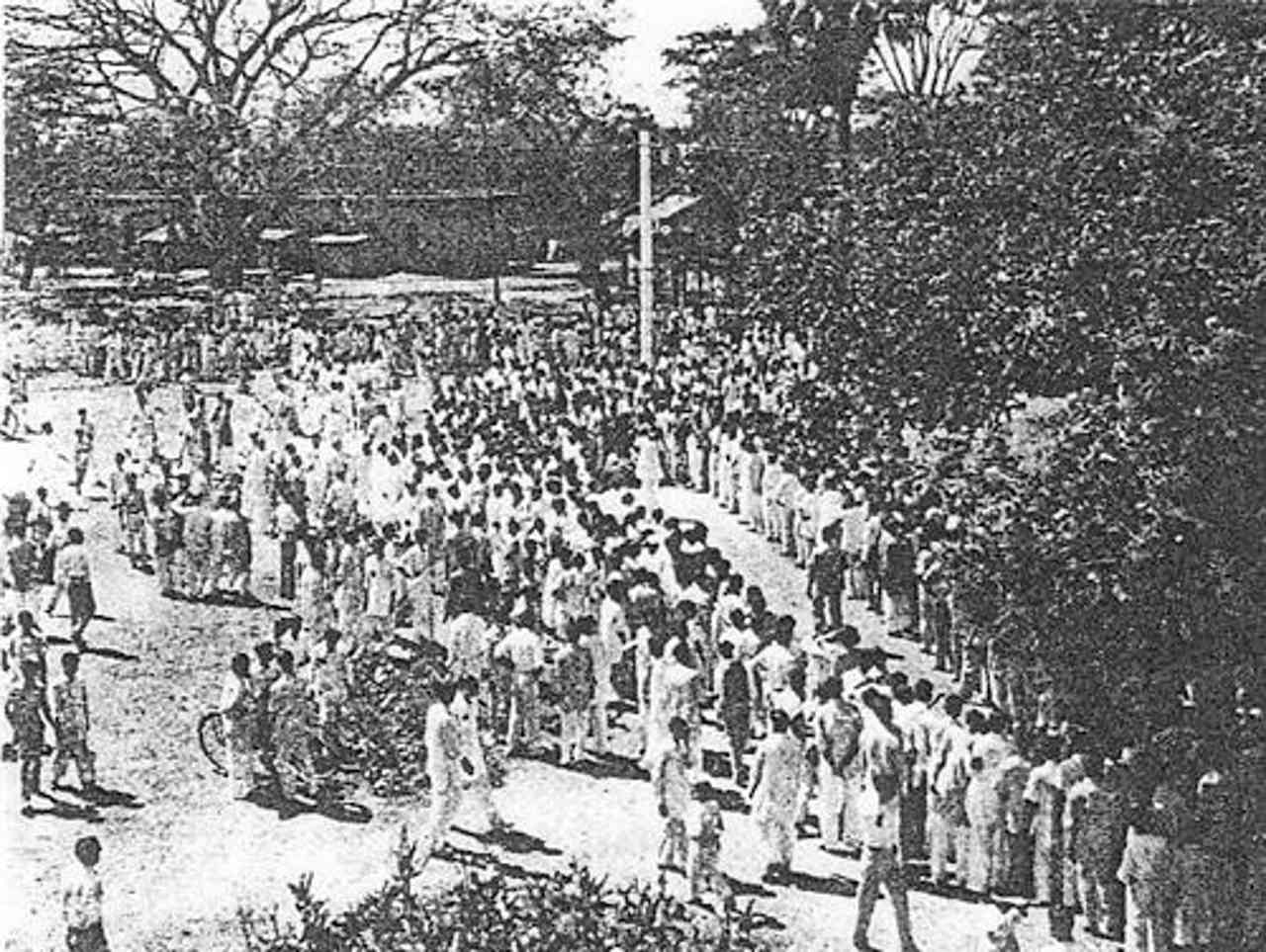

Worker Vanguards Embrace Communism

The 1920s saw an infectious rise of political activism in almost all major working-class centres. New states joined the map of the working class movement. In May 1921, tea gardens of Assam, especially at Chargola in Surma valley witnessed a major upsurge of tea workers leading to a massive exodus of some 8,000 workers from the valley. Sporadic struggles were again reported in December 1921 from the tea gardens of Darrang and Sibsagar districts. On November 17, 1921, workers in Bombay, Calcutta and Madras played a key role in organising a highly successful countrywide hartal (general strike) in protest against the visit of the Prince of Wales. Madras had just witnessed a bitter four-month-long strike from July to October at the Buckingham & Camatic Mills. As many as seven workers were killed by the police in the course of this strike. On 1 May, 1923, elderly Madras lawyer and labour leader Singaravelu Chettier organised the first major May Day celebration in India on the Madras beach. Singaravelu was critical of the repeated brakes applied by Gandhi on the non-cooperation movement and went on to be among the communist pioneers in the country. North Western Railway witnessed a major strike lasting from April to June 1925. Textile strikes, of course, continued to rock Bombay at regular intervals.

May Day rally. WIKIMEDIA COMMONS

This was also the period that saw the beginning of introduction of communist ideology in the Indian working class movement. Communist circles began to operate among Indian expatriates as well as inside the country. On December 26, 1925, leaders of various communist circles active in the country met at Kanpur and formally launched the Communist Party of India. In the 1920s, communists also operated from within organisations called workers’ and peasants’ parties apart, of course, from the Congress. Such parties became quite active and popular in Bengal, Bombay, Punjab, UP and Delhi. In Punjab the party was known as the Kirti Kisan Party and was formed at Jallianwallah Bagh in Amritsar on the ninth anniversary of the infamous massacre.

Workers Demand Complete Independence

To stem the rising tide of working class movement, the British government came up with the highly restrictive Trade Unions Act legislation in 1926. This Act virtually declared all unregistered unions as illegal and placed all sorts of restriction on trade unions collecting and contributing funds for political purposes. Ironically, this was in sharp contrast to the prevailing norms in Britain where trade unions formed the backbone of the Labour Party and played a key role in the country’s politics. But this retrograde and restrictive piece of hypocritical legislation could hardly dampen the rising spirit of working class movement.

In February 1928, 20,000 workers marched in Bombay against the arrival of the all-white Simon Commission. The Lilooah rail workshop witnessed a major struggle from January to Jury 1928, From 18 April to September 1928, T1SCO workers went on a protracted strike. Bombay had yet another massive textile strike from April to October 1928. July 1928 saw a brief but very bitter strike on the South Indian Railway. Its leaders, Singaravelu and Mukundlal Sircar, got jail sentences while a worker striker, Perumal, was extemed for life to the Andamans. The most spectacular assertion of the working people could be seen in Calcutta where in December 1928, thousands of workers led by the Workers’ and Peasants’ Party of Bengal marched into the Congress session, occupied the pandal for two hours and adopted resolutions demanding Purna Swaraj or complete independence.

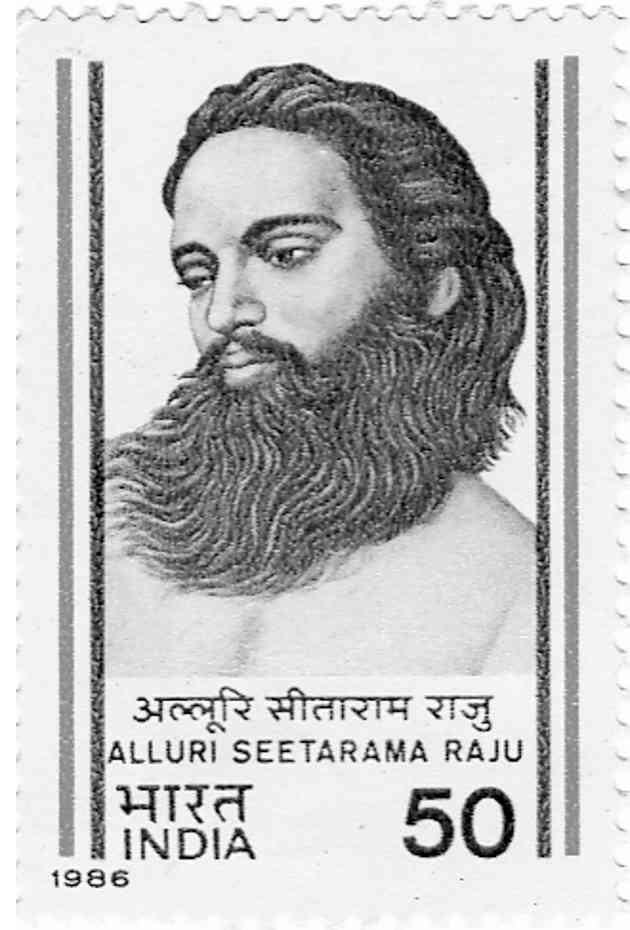

Alluri Sitarama Raju to Bhagat Singh: Inquilab Zindabad

The beginning of the 1920s had witnessed a great example of peasant guerrilla war in Andhra. From August 1922 to May 1924, Alluri Sitarama Raju and his band of hundred tribal peasant guerrillas waged a successful war against the British state over an area of about 2,500 square miles in the hills of the Godavari Agency region. With his accurate ambushes and successful raids on police stations, Raju won the grudging admiration of the British as a formidable guerrilla tactician. The Madras Government spent Rs. 15 lakh to suppress the rebellion with the help of the Malabar Special Police and the Assam Rifles. Raju was finally caught while he was bathing in a pond, and after inflicting heavy torture on this great fighter the British administration shot him dead on 6 May 1924. Incidentally, the fiftieth anniversary of India’s independence also marks the birth centenary of this legendary peasant revolutionary.

If Alluri Sitarama Raju symbolised the courage and capacity of the rural poor to wage a militant battle for independence, Bhagat Singh held out a really potent promise of a much more meaningful freedom that could have been ours. In September 1928, he and his comrades set up the Hindustan Socialist Republican Army at a meeting held on the ruins of Delhi’s Ferozeshah Kotla. In one of its first actions, the HSRA avenged the assault on Lajpat Rai (he was seriously injured by the police white leading an anti-Simon protest march at Lahore on 30 October, 1928 and finally succumbed to death on 17 November) by killing the guilty police official Saunders at Lahore in December 1928. On 8 April, 1929 Bhagat Singh and Batukeswar Dutta threw bombs in the Legislative Assembly even as discussion was on in the Assembly on the anti-labour Trades Disputes Bill and a bill to bar British communists and other supporters of Indian independence from coining to India.

While carrying out such specific terrorist actions under the HSRA banner, Bhagat Singh and his comrades also built up an open youth organisation in the name of Naujawan Bharat Sabha. The clarion call popularised by Bhagat Singh, Inquilab Zindabad, has become the permanent war cry of every Indian struggle for justice, freedom and democracy.

Inquilab Zindabad!

It takes a loud voice to make the deaf hear. With these immortal words uttered on a similar occasion by Valliant, a French Anarchist martyr, do we strongly justify this action of ours.

Without repeating the humiliating history of the past ten years ... we see that this time again, while the people expecting some more crumbs of reforms from the Simon Commission are ever quarreling over the distribution of the expected bones, the Government is thrusting upon us new repressive measures like the Public safety and Trades Disputes Bills while reserving the Press Sedition Bill for the next session. The indiscriminate arrests of labour leaders working in the open clearly indicates whither the wind blows.

In these extremely provocative circumstances, the HSRA in all seriousness, realising their full responsibility, had ordered its army to do this particular act so that a stop be put to this humiliating farce....

Let the representatives of the people return to their constituencies and prepare the masses for the coming revolution. And let the Government know that while protesting against the Public Safety and the Trades Disputes Bills and the callous murder of Lala Lajpat Rai, on behalf of the helpless Indian masses, we want to emphasise the lesson often repeated by history that it is easy to kill individuals but you cannot kill ideas. Great empires have crumbled while ideas have survived. The Bourbons and the Czars fell, while revolutions marched triumphantly over their heads. ... Long Live Revolution.

- Excerpts from the leaflet issued by Bhagat Singh and Batukeshwar Dutt while throwing bombs in the Legislative Assembly on 8.4.1929

Sholapur Commune and Chittagong Armoury Raid

From 12 March to 6 April, Gandhi accompanied by 71 inmates of his ashram drawn from different parts of the country undertook the famous Dandi March. The issue of salt served as a simple yet very potent rallying point and the movement soon assumed a countrywide mass dimension. The arrest of Nehru in the middle of April led to bitter clashes between mill workers at Budge Budge near Calcutta and the police. The mood of the jute mill workers of Bengal was then quite upbeat, only the previous year they had organised a highly successful general strike in jute mills to beat back the employers’ bid to increase working hours from 54 to 60 hours a week. Calcutta transport workers too waged a militant struggle. A major upsurge was also witnessed at Peshwar in North Western Frontier Province. The city continued to be rocked for ten days on end following the arrest of Badshah Khan (the Frontier Gandhi) and other leaders on 23 April, 1930 leading to the imposition of martial law on May 4. Refusal by the Garhwal regiment led by Chandra Singh Garhwali to open fire on peaceful demonstrators at Peshawar opened up a new possibility of fraternisation between the fighting people and the armed forces. Dock labourers in Karachi and Choolai Mill workers in Madras were also up in arms.

Lenin Day in Lahore Court

Before proceedings commenced today in the Lahore Conspiracy case, all the eighteen accused who entered the Court room with red scarves round their necks took their seats in the dock amidst shouts of Long Live Revolution’, ‘Long Live the Communist International’. ‘Long Live Lenin’, ‘Long Live the Proletariat’ and ‘Down, Down with Imperialism’.

Bhagat Singh informed the Magistrate that he and his fellow accused were celebrating the day as Lenin Day and requested him to convey the following message to the President. Third international at Moscow at their cost. The message runs: On the occasion of the Lenin Day we express brotherly congratulations on the triumphant march of Comrade Lenin’s mission. We wish every success for the great experiment carried on in Soviet Russia. We wish to associate ourselves with the world revolution movement. Victory to Workers’ Regiment. Woe to the Capitalists Dawn with Imperialism...

- Hindustan Times, 26 January, 1930

The climax came at Sholapur following Gandhi’s arrest on 4 May. The entire work force in the textile industry went on strike from 7 May onward. Till martial law was clamped down on 16 May, the town remained virtually under workers’ control. Liquor shops were burnt down and police outposts, law courts, the municipal building and the railway station all came under attack. Something like a parallel government seemed to have token over the entire township and if soon became well-known across the country as the celebrated case of the Sholapur Commune.

Surya Sen’s Appeal

Dear Soldiers of Revolution,

The great task of Revolution in India has fallen on the Indian Republican Army.

We, in Chittagong. have the honour to achieve the patriotic task of Revolution for fulfilling the aspirations and urge of our nation....

I, Surya Sen, President of the Indian republican army, Chittagong Branch, do hereby proclaim the existing Council of the Republican Army in Chittagong to form itself into a Provisional Revolutionary Government to carry out the following urgent tasks:

1. To defend and maintain the victory gained today;

2. To extend and intensify the armed struggle for National Liberation;

3. To suppress the enemy agent within;

4. To keep the criminals and looters in checks;

5. And to take further course of action that this Provisional Revolutionary Government will decide later.

This Provisional Revolutionary Government expects and demands full allegiance, loyalty and active cooperation from every true son and daughter of Chittagong....

With full confidence in victory in our Holy War of Liberation.

No mercy to the British Bandits! Death to the traitors and looters!

Long live Provisional Revolutionary Government!

— Surya Sen made this appeal after the first round of

Chittagong action on 18 April, 1930

Congress Rule in Provinces: An Early Pointer

The twenty-seven months of Congress rule in the provinces served as a clear early pointer to the conservative character of the Congress-led social coalition. A whole set of democratic demands of the working class and the peasantry had already come to be articulated not only by the AITUC and the All India Kisan Sabha (formed in Lucknow in April 1936 under the presidentship of Swami Sahajanand Saraswati) but also in various AICC sessions and by the Bihar and UP PCCs. The Congress governments in the provinces refused to take any significant step in this direction.

The betrayal was perhaps most glaring on the working class front. While in Bengal, the Congress Working Committee expressed solidarity with the jute workers who went on a massive general strike from March to May 1937 and denounced the non-Congress Fazlul Haq ministry for adopting repressive measures, similar measures continued to be freely applied by Congress ministries in other provinces. In Assam, during the Digboi oil strike of 1939 against the British-owned Assam Oil Company, the Congress ministry led by N C Bordoloi allowed free use of the war lime Defence of India rules to crush the strike. And in Bombay, the Congress ministry rushed through the Bombay Trades Disputes Act in November 1938 which was far worse than the earlier 1929 version of the Act. It imposed compulsory arbitration thereby making virtually all strikes illegal and raised the prison-penalty for illegal strikes from three months to six months. The Bombay Governor found the Act “admirable” white Nehru found it “on the whole ... a good one”. Barring the Gandhian labour leaders of Ahmedabad, the entire trade union movement opposed this draconian Act; 80,000 workers attended a protest rally in Bombay on 6 November addressed among others by Dange, Indulal Yajnik and Ambedkar and the next day the entire province observed a general strike.

Quit India: Unprecedented Countrywide Upsurge

On 8 August, 1942, at Gandhi’s behest the Congress Working Committee adopted the famous Quit India resolution calling for “mass struggle on non-violent lines on the widest possible scale”. Anticipating immediate arrest of the Congress leadership, the resolution even asked “every Indian who desires freedom and strives for it ... (to) be his own guide”. Gandhi delivered his celebrated “Do or die” speech and for once even went to the extent of saying “if a general strike becomes a dire necessity, I shall not flinch”.

All Congress leaders were arrested and removed by the early morning of August 9. With the British unleashing wholesale repression, almost the entire country exploded in violent protests.

What eventually came to be known as the great Quit India rebellion was thus a largely spontaneous outburst, led in pockets by socialist leaders working underground and local-level Congress activists. Bombay and Calcutta were rocked by continuous strikes. Striking workers clashed with the police in Delhi, and in Patna, control over the city was virtually lost for two days following a major confrontation in front of the Secretariat on 11 August. The Tata steel plant was completely closed down for 13 days from 20 August with the TISCO workers refusing to resume work till a national government was formed. Ahmedabad textile workers were also on strike for no less than three and a half months. As many as 11 B & C Mills workers died in police firing in Madras.

The Tumultuous Forties

To prevent any repetition of a mass upsurge on the Quit India scale and best preserve their long-term interests in India, Britain quickly initiated the process of negotiations for the eventual transfer of power. Indian capitalists were also in great hurry to have an early transfer primarily because they were afraid that delay would only raise the profile of the working class and the communists in the future alignment of forces in free India. The fear of a revolution was quite real both for British imperialists and their would-be Indian successors.

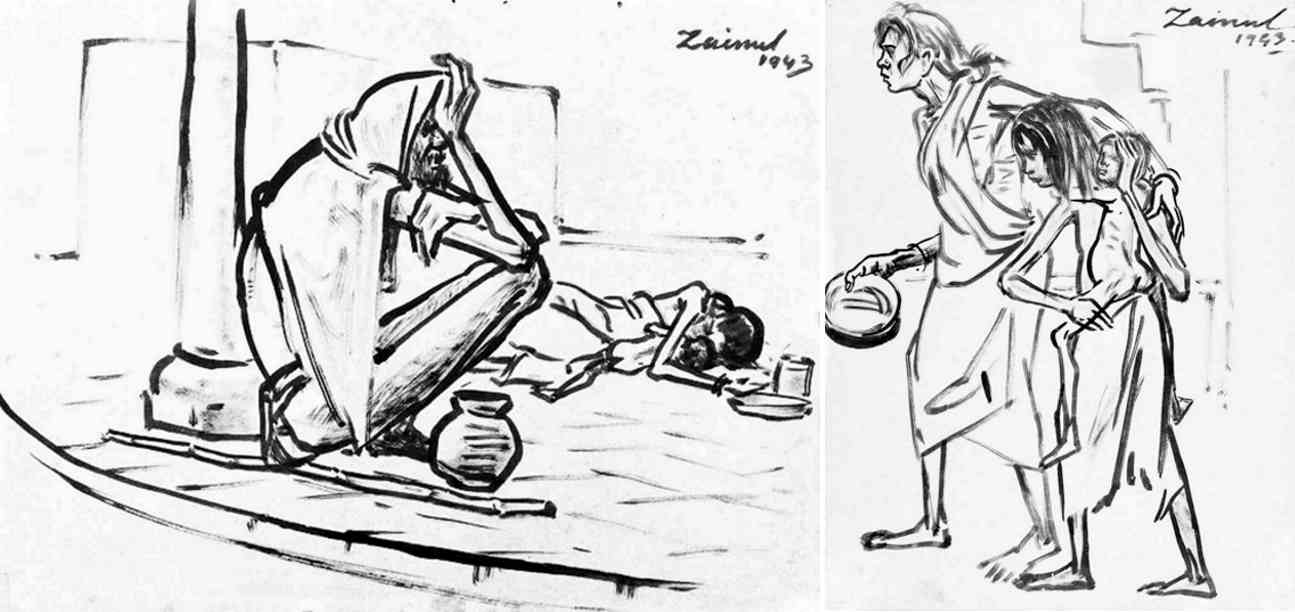

After the ill-conceived isolation of 1942, communists were soon back in mass action in a big way. With exemplary zeal and dedication, the Communist Party organised massive relief operations in the wake of the severe 1943 famine. Mention must be made here of the excellent role played in this relief work as well as in all subsequent mass upsurges by the communist-led progressive cultural activists of the Indian People’s Theatre Association.

In an increasingly communally surcharged situation when almost all established leaders were busy angling for their own loaves of power, the working people marching and fighting under the great red banner were the only force to uphold the ideals of communal harmony and secularism, selfless sacrifice and progressive anti-imperialist nationalism.

INA Trials and the Great Naval Mutiny of Bombay

On 21 October, 1943, when the Second World War had nearly entered its last phase, Subhas Chandra Bose issued his famous Delhi Chalo call from Japanese-controlled Singapore. He announced the formation of the Azad Hind Government and the Indian National Army, the latter had rallied about 20,000 of the 60,000 Indian prisoners of war in Japan. Between March and June 1944 the INA made its brief entry into India, laying siege to Imphal along with Japanese troops. But this campaign ended in an utter military failure even though it had a great psychological impact on the popular Indian mind.

In November 1945 British rulers began public trial of INA soldiers in Delhi’s Red Fort. This provoked a very powerful and determined wave of protests in Calcutta. On 20 November, students took out nightlong procession demanding release of INA prisoners and when two students were killed in police firing, thousands of taxi drivers, tram workers and corporation employees joined the students. Pitched battles were fought on Calcutta streets on 22-23 November leaving 33 people killed in police firing. Between 11 and 13 February, Calcutta was shaken by a second wave of protests when Abdul Rashid of INA was sentenced to seven years’ rigorous imprisonment 84 people were killed and 300 injured during these three days of street battle.

While Calcutta exploded in protest over the INA trials, Bombay was rocked by the heroic naval mutiny. The sequence of events had a close resemblance to the Black Sea Fleet mutiny in the Russian revolution of 1905 which has been immortalised by the great Russian film director Sergei Eisenstein in his all-time classic Battleship Potemkin. In India there has been no film on the Bombay mutiny, but playwright director Utpal Dutt did pay tribute to the great naval fighters in his inspiring play Kallol in the 60s.

On 18 February, 1946, ratings in the Bombay signalling school Talwar went on hunger-strike against bad food and racist insults. The strike soon spread to Castle and Fort Barracks on shore and 22 ships in Bombay harbour raised the Congress, League and Communist flags on the mastheads of the rebel fleet. The Naval Central Strike Committee combined issues like better food and equal pay for white and Indian sailors with the demands of release of INA and other political prisoners and withdrawal of Indian troops from Indonesia. On 21 February, fighting broke out at Castle Barracks when ratings tried to break through the armed encirclement. By 22 February the strike had spread to naval bases all over the country involving no less than 78 ships, 20 shore establishments and 20,000 ratings.

The Bombay unit of CPI, supported by Congress Socialist leaders like Aruna Asaf Ali and Achyut Patwardhan organised a general strike on 22 February and despite Congress and League opposition 30,000 workers struck work, almost all mills were closed and according to official figures 228 people were killed and 1046 injured in street fighting. Senior Congress leaders only intervened to end the mutiny. On 23 February, Patel succeeded in persuading the ratings to surrender on the assurance that their demands would be conceded and nobody would be victimised. But the assurance was soon forgotten with Patel pointing out that “discipline in the Army cannot be tampered with”, Nehru emphasising the need to curb “the wild outburst of violence” and Gandhi condemning the ratings for setting bad “an unbecoming example for India”.

The Great Working Class Actions of July 1946

1946 also saw a massive wave of working class struggles and peasant insurgency crossing all previous records. The strike-wave this year recorded 1629 stoppages involving 1,941,948 workers. And with government employees too throwing in their full weight, strikes increasingly became all-India affairs. Most significant in this context was the July strike of postal and telegraph employees. On July 11, 1946, the Postman Lower Grade Staff Union went on an indefinite strike. The All India Telegraph Union too joined in. By July 21, posts and telegraph employees all over Bengal and Assam also threw in their lot. Bombay and Madras observed solidarity industrial strikes on July 22 and 23 respectively. On July 29, general strike was observed in Bengal and Assam.

The same day, Calcutta witnessed a massive rally, which has perhaps had very few parallels since in terms of spontaneous mass involvement, firm in its belief that “this historic general strike has marked the beginning of a new chapter of unity and fighting consciousness in the labour movement of the country”. The strike wave continued in 1947 with Calcutta tram workers striking work for 85 days. Kanpur, Coimbatore and Karachi also emerged as prominent centres of working class action.

Tebhaga, Punnapra-Vayalar, Telengana ...

This was also the peak period for the Communist-led peasant movement. Soon after the Calcutta communal killings of August, in September 1946, the Bengal unit of Kisan Sabha launched the popular tebhaga agitation demanding two-thirds crop share for the sharecropper. North Bengal emerged as the storm centre of this militant and immensely popular peasant upsurge. Apart from Thakurgaon sub-division of Dinajpur and neighbouring areas of Jalpaiguri, Rangpur and Malda districts of North Bengal, the tebhaga movement also acquired great depth in Mymensingh (Kishoreganj), Midnapur (Mahisadal, Sutahata and Nandigram) and 24 Parganas (Kakdwip) districts in the rest of Bengal.

In the Travancore-Cochin belt of Kerala, communists had already developed a strong base among coir factory workers, fishermen, toddy-tappers and agricultural labourers. In 1946 as the rulers of this princely slate started toying with the idea of introducing the so-called American model of presidential system communists vowed to throw the American model into the Arabian sea. Severe repression was unleashed on communist activist in Alleppey region. Against this backdrop a political general strike began in the Alleppey-Shertalai area from 22 October and on October 24, a partially successful raid was carried out on the Pimnapra police station. Martial law was clamped down on 25 October and on 27 October, the armed forces stormed the volunteer headquarters at Vayalar near Shertalai after A veritable bloodbath According to conservative estimates, at least 800 people were killed in this rather short-lived Punnapra-Vayalar uprising.

If Punnapra-Vayalar was short-lived, Telengana, lasting from July 1946 to October 1951, provided the classic example of protracted communist-led peasant guerrilla war. The uprising began on 4 July 1946 when the henchmen of one of the biggest and most oppressive Telangana landlords killed a village militant, Doddi Komarayya in Jangaon taluka of Nalgonda district who had been trying to defend a poor washer-woman’s small piece of land. Spreading from the Jangaon, Suryapet and Huzurnagar talukas of Nalgonda, the flames of peasant resistance soon engulfed the neighbouring Warangal and Khammam districts.

Armed guerrilla squads began to take shape from early 1947 in the face of brutal repression. The struggle reached its zenith between August 1947 and September 1948. At its peak, the Telengana uprising covered three million people in 3,000 villages spread over 16,000 square miles. There were 10,000 village defence volunteers and 2,000 regular squad members. Like tebhaga, Telengana too had a high degree of women’s participation which made a signal contribution to the movement’s overall impact. In his account of the Telengana struggle, P Sundarayya, who was one of its key leaders, has described the great emancipating and multi-dimensional impact of the movement particularly in the liberated areas, ranging from implementation of basic land reforms and betterment in the conditions of the rural poor to improvement in the status of women and spread of progressive social and cultural values. But most importantly, Telengana pulsated with a tremendous revolutionary spirit and symbolised the first major and comprehensive application of revolutionary communist strategy in India.

Telengana also held an accurate mirror to the actual nature of the transition that took place in 1947. While an oppressed peasantry continued to fight for thoroughgoing land reforms and complete overthrow of feudalism without which a predominantly agricultural country like India could never have real freedom, the Congress government banned the Communist Party and rushed in its army to quell the rebellion in September 1948. According to a conservative estimate at least 4,000 communist fighters and peasant militants were killed in the course of the Telengana uprising and at least another 10,000 subjected to indescribable physical torture, many of whom eventually succumbed to death.

Having already allowed the country to be partitioned on communal lines, the “Iron Man” of modern India, Sardar Patel embarked on his mission to integrate a partitioned India. The powerful State People’s Movement and uprisings like Punnapra-Vayalar and Telengana had already shaken the foundation of the 600-odd princely states Patel completed the job of integrating these states by offering lucrative privy purses to the “dispossessed” princes. Several members of this princely tribe were also respectfully accommodated in the emerging dispensation of power and privileges as Governors, Ministers and “Dignitaries” with diverse designations.

The Working Class And Peasantry Today

In the 75 years of independence, India’s working class and peasantry have waged many battles, and wrested a measure of rights from the capitalists and landlords that rule India. But today, each hard-won right is under a lethal attack from the current rulers who are descendants of the RSS and Hindu Mahasabha that betrayed the freedom struggle and served the British rulers back then. Today in their labour laws, working conditions, treatment of union leaders and working class movements, they mirror the colonial “Company Raj”, serving corporations and sacrificing workers. The Modi regime tried to hand over India’s entire agriculture sector to corporations, with its Three Farm Laws, which a determined year-long struggle by farmers succeeded in pushing back. And at the same time, the current regime tries not only to replicate the colonial “Divide and Rule” policy but to dismantle India’s constitutional democracy and hard-won freedom and replace it with fascist oppression under the garb of “Hindu Rashtra” within the country, together with subservience to US imperialism.

During the freedom struggle, workers and peasants again and again rebuffed divisive communal politics and united to deliver spirited blows to the colonial rulers. Now, once again, India’s workers and peasant must rise to the challenge, resist every attempt to poison the well of people's unity with anti-Muslim venom, and unite to defend India’s democracy and freedom.

Impressions 1946

There’s rebellion today

Rebellion on every side,

And I’m here

Recording its daily diary,

No-one has ever seen

Such rebellion,

Waves of defiance

Swelling in every direction;

All of you, come down

From your castles in the air –

Can you hear it?

A new history

Is being written by strikes,

Its covers engraved in blood.

Those who are daily despised

And downtrodden

Look – today they are all prepared

Swiftly moving forward together;

And I too am there behind them,

That’s why I’m carrying on

Recording this daily diary –

There’s rebellion today!

Revolution on every side!!

– Sukanta Bhattacharya (1926-1947)