A Crow in Peacock Feathers?

OUR GOVERNMENT of course does not accept the very existence of any IMF-laid debt trap or the fact that a package of IMF conditionalities is being imposed on us. Obediently implementing the IMF-World Bank blueprint of shock therapy, it is absorbed in capitalising on the climate of crisis and 'the potentially short-lived, but broad mandate' the crisis is assumed to have conferred on the government to thrust structural reforms down our throats. And the 'reforms', we are promised, would usher us into an era of rapid export-led growth and awaken all the slumbering potential of industrialisation in India to pitchfork the country from its present company of low-income economies to the prestigious club of the newly industrialised Asian countries like South Korea, Taiwan, Singapore and Hong Kong!

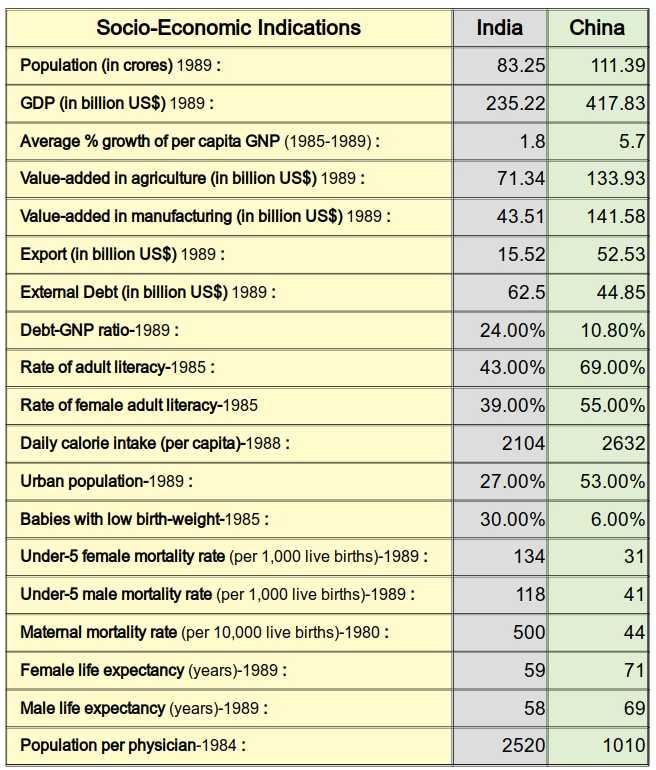

It is tragic that instead of comparing India with China, the only Asian country with which we can naturally and logically compare ourselves, Indian rulers have started bracketing the second largest country of the world with city-states like Singapore and Hong Kong! We say the comparison with China is both natural and logical because of our broad similarity in terms of population size and most other basic socio-economic indicators, and also because of the fact that our two countries have followed two different paths to economic development. Like India, China is still regarded as a low-income Third World economy and yet, as the accompanying chart indicates, in terms of many development indicators and quality of life, China has left us far behind and is racing close to the standard of advanced nations.

Socio-Economic Indications

Source : World Development Report, 1991

The difference that stands out most glaringly in any comparison of the developmental profiles of China and India is that China has not only grown faster but mere importantly, the gains of economic growth there have been distributed far more evenly while in India they have been monopolised entirely by the upper echelons of the society. Yet, all talk of equitable development and distributive economic justice has become taboo in India. Economic growth is worshipped as the sole idol and development is treated as the growth-god's benign blessings trickling down to the community of believers.

Even leaving apart the crucial distinction between growth and development, if we just look at the claims of establishment economists from their own premise of emulating the South Korean and Taiwanese experience, we find any number of gaps in the whole framework. To take just one obvious instance, both South Korea and Taiwan were recipients of abundant foreign patronage and aid, first from Japan in the first half of this Century and subsequently from the United States in the 50s and 60s when the latter was obsessed with protecting its spheres of influence from the Socialist appeal of China and North Korea. The case of post-World War II economic reconstruction of war-ravaged Western Europe with abundant US aid under Marshall Plan also rested on the same political premise. The India of 90s is simply not placed in that kind of circumstances. However much we may agree to bend or crawl before foreign capital and technology, no industrial power is willing to leave an inch of its market or spend an iota of its economic surplus to sponsor economic growth in India.

The second and a more basic point to realise is that a crow can never aspire to become a peacock except through fundamental genetic changes. Putting on a few borrowedor stolen feathers will simply not help. There are five global lessons of growth which have to be learnt before letting our imagination fly wildly.

- No economy can take off without a vibrant domestic market. Export-led growth is sheer myth, more so for countries with a huge agricultural population.

- The key to a vibrant home market lies in extensive land reforms, agricultural development and extension service.

- No country has grown without the right investment in its people, in the health, housing and education of its present and future citizens.

- Free market, free trade and perfect competition are plain lies, no economy has ever grown without substantial state Intervention and protection of domestic industry and workforce from unequal foreign competition.

- All success-stories of economic growth are tributes to the strong patriotic or nationalist motivation of the people and government of those countries.

And what is our record on these counts?

Domestic Market: Industrial structure remains heavily 'import-dependent. Enormous potential of rural industrialisation virtually untapped. Monopoly stranglehold over market preventing decentralised and all-round growth. Commodities of mass consumption increasingly ignored.

Rural Reforms: Out of a total operated area of 162.8 million hectares only 26 million hectares identified as ceiling-surplus, of which only 2.4 million hectares taken over and just 1.8 million hectares actually distributed. 95% loans of agricultural labourers and artisans still in the grip of private moneylenders.

Agricultural Development: 70% of cultivated area without any irrigation facility. Low yield of crops and poor utilisation of arable land. Stagnation in output of pulses. Continued dependence on import of edible oil.

Investment in People: Of the total annual expenditure of central government, only 2.7% goes to education, 1.7% to health and 5% to housing, amenities, social security and welfare while defence gets 17%.

Patriotic Motivation: Bureaucracy and elite still suffering from colonial hangovers with Swiss banks remaining the Mecca for Indian businessmen and emigration to the US, the ultimate dream of the academic elite. Cost of brain drain alone estimated at $ 51 billion between 1967 and 1985.